There is a specific kind of American optimism that borders on the pathological. It is the same impulse that leads us to believe we can learn French in a weekend, or that eating a single kale salad will reverse a decade of chili cheese fries. In the legal world, this optimism manifests most tragically in the filing of the Provisional Patent Application (PPA).

The premise is seductive, like a low-interest credit card offer in the mail. For a nominal fee, you can secure a "Priority Date"—a temporal flag in the sand that says, I was here first. You don't need formal claims. You don't need an oath. You can, theoretically, staple a cocktail napkin to a cover sheet and mail it to the Patent Office in Alexandria, Virginia.

However, this perceived informality has mutated into a significant liability for inventors, startups, and corporations alike. A widespread misconception persists that a provisional application can be a "rough draft," a "napkin sketch," or a mere "intent to patent."

This blog posts analyses, through legal analysis and case studies, that this belief is not only erroneous but commercially fatal.

The legal standards governing the sufficiency of a provisional application—specifically the written description and enablement requirements of 35 U.S.C. § 112(a)—are indistinguishable from those applied to issued patents. When a provisional application fails to meet these standards, it effectively evaporates. The priority date is lost, and the applicant is exposed to a barrage of invalidating "intervening art," including their own public disclosures, sales, and competitor filings.

The cases discussed here underscore a singular, urgent conclusion: the quality of a provisional application is an important determinant of a patent portfolio’s long-term survivability.

Why "Informal" Does Not Mean "Incomplete"

Let's get the boring, imminently skippable section out of the way first (unless you are a legal nerd, like we are, or you are into origin stories).

The Genesis and Purpose of the Provisional Application

To understand why your provisional application can become a loaded gun pointed at your own foot, we must briefly discuss their statutory origin and function.

Prior to 1995, the United States operated largely on a "first-to-invent" system, where an inventor could rely on sworn logbooks and testimony to prove an earlier date of invention, even if they filed their application later than a competitor. The adoption of the provisional application system was part of the U.S. effort to move toward a "first-to-invent" (and later "first-to-file" under the America Invents Act) framework while offering a mechanism to establish a priority date comparable to foreign systems.

Under 35 U.S.C. § 111(b), a provisional application allows an applicant to file a specification and drawings without formal patent claims, an oath or declaration, or an Information Disclosure Statement (IDS). It provides a 12-month pendency period during which the applicant can file a corresponding non-provisional application under 35 U.S.C. § 111(a) claiming the benefit of the provisional’s filing date pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 119(e).

Crucially, the provisional application is never examined by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). It sits in a dormant state until it is either abandoned (after 12 months) or referenced by a non-provisional application. This lack of examination contributes to the dangerous false confidence that a "thin" or poorly drafted provisional is sufficient. Because the USPTO does not issue rejections against provisionals, inventors do not discover the fatal defects in their application until years later—often during high-stakes litigation or after a patent has issued and is challenged.

The "Four Corners" of 35 U.S.C. § 112(a)

The statutory bridge that connects a provisional application to a later-issued patent is 35 U.S.C. § 119(e)(1). This section grants the benefit of the earlier filing date only if the invention claimed in the non-provisional application is disclosed in the provisional application "in the manner provided by the first paragraph of section 112."

Section 112(a) (formerly the first paragraph) imposes three distinct but interrelated disclosure requirements:

Written Description: You must prove you "possessed" the invention.

Enablement: You must teach a person of ordinary skill how to make it.

Best Mode: You cannot hide the secret sauce.

The great tragedy of the modern inventor is the belief that a provisional application is a "rough draft." You think: I’ll just jot down the general idea now, and my attorney can add the circuit diagrams and the chemical formulas next year when we file the Non-Provisional.

This is incorrect.

If you file a provisional that says "A system to cure baldness using lasers," and a year later you file a Non-Provisional describing the specific frequency and pulse duration of those lasers, you have a problem. The specific details in the new filing constitute "New Matter." They do not get the date of the provisional. They get the date of the new filing.

This creates a scenario of bifurcated priority:

Subject Matter A (Disclosed in Provisional): Effective Filing Date = January 1, 2024 (Provisional Date).

Subject Matter B (Added in Non-Provisional): Effective Filing Date = January 1, 2025 (Non-Provisional Date).

If the patent claims rely on Subject Matter B for patentability (e.g., to distinguish over prior art), the effective date of the patent is January 1, 2025. This 12-month gap is the "Kill Zone." Any public disclosure, sale, or competitor filing that occurred between Jan 1, 2024, and Jan 1, 2025, becomes intervening prior art. If the inventor published a white paper in June 2024, that white paper is may become prior art against their own patent in certain jurisdictions.

The Doctrine of Possession vs. Enablement

It is important to distinguish between enablement and written description, as a "thin" provisional often fails the latter even if it passes the former. As elucidated in Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., enablement allows someone to make the invention, but written description proves the inventor invented it.

Consider a provisional that states: "The system uses a software algorithm to optimize battery life by 50%."

Enablement: A skilled software engineer might be able to read this and, with enough time and effort, write an algorithm that achieves this.

Written Description: The provisional fails because it does not describe which algorithm the inventor had in mind. It describes a problem and a desired result, not the solution. Therefore, a later claim to a specific "heuristic scheduling algorithm" will not get the priority date, because the provisional did not show possession of that specific heuristic.

This distinction is the graveyard of many provisional applications, particularly in the biotech and software sectors, where functional descriptions ("a means for doing X") are often substituted for structural descriptions ("a code segment comprising steps A, B, and C").

Capisci? Good. Let's get to the stuff that brought you to this blog post in the first place:

Case Studies: How Do These Problems Manifest Themselves?

The abstract risks of § 112 deficiencies are made concrete through the ruthless scrutiny of the courts. The following detailed case studies illustrate specific modes of failure in provisional drafting and the resulting destruction of patent rights.

The Fast Provisional Problem

New Railhead Mfg., L.L.C. v. Vermeer Mfg. Co., 298 F.3d 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2002)

The invention was a drill bit for boring under rocks. It was a good drill bit. It had a specific geometry—the bit body was "angled with respect to the sonde housing." This angle was the whole point. It was the invention.

The inventor, Mr. Cox, filed a provisional application. He was likely in a hurry. Perhaps he had a trade show to get to, or perhaps he just wanted to save a few dollars on legal fees, a decision that belongs to the genus of "stepping over dollars to pick up dimes." In his provisional, he described the drill bit. But he did not explicitly describe the angle. He didn't draw the angle. He assumed, perhaps, that anyone looking at the device would see the angle and understand.

He sold the drill bits. Time passed. He filed a formal "Non-Provisional" application that did describe the angle.

Critically, the non-provisional was filed more than one year after the first sale.

Thereafter, he got his patent. He sued a competitor (Vermeer).

When New Railhead sued Vermeer for infringement, Vermeer challenged the validity of the patent. Vermeer argued that the patent was invalid because the invention had been on sale for more than a year before the non-provisional filing date. New Railhead countered that they were entitled to the provisional's filing date, which was within the grace period.

The Federal Circuit sided with Vermeer. The court analyzed the provisional application and found that the disclosure of the "angled" feature was missing. The court rejected the argument that a person skilled in the art would "inherently" understand the angle was necessary. Because the provisional did not satisfy the written description requirement for the "angled" limitation, the claims were not entitled to the provisional's date.

The Result: The effective filing date of the patent shifted to the non-provisional date. Because this date was more than one year after the first sale, New Railhead's own sale became invalidating prior art. The patent was declared invalid.

He had invented a machine to bore through rock, but he failed to bore through the bedrock of Section 112. The patent was dead. The monopoly was gone.

Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt, except for the millions of dollars in lost revenue.

The Broad Provisional Problem

DDR Holdings, LLC v. Priceline.com LLC, 773 F.3d 1245 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

After reading the above, you may be thinking, "easy" I'll just write very broad provisionals and lay the groundwork for every angle possible. Here's how the inverse problem shows up: DDR Holdings sued Priceline over a patent for e-commerce outsourcing systems. A key term in the claims was "merchant."

The Provisional/Non-Provisional Discrepancy In the provisional application, "merchant" was defined broadly to include sellers of "products or services." However, in the non-provisional application, the definition was changed to remove the reference to "services," referring only to "goods."

In a 2024 decision revisiting this family of patents , the Federal Circuit held that the narrowing of the definition in the non-provisional was a surrender of scope. Even though the provisional had the broader scope, the conscious decision to remove "services" in the transition to the non-provisional meant the patentee could not later argue that "merchant" covered service providers like Priceline (who sell travel services, not goods).

A finding of non-infringement. While this is the inverse of the New Railhead problem (here the provisional was broad, but the non-provisional narrowed it), it illustrates that the relationship between the two documents is subjected to forensic linguistic analysis. Inconsistencies between the two are invariably resolved against the patentee.

The "Thin" Provisional Problem

PowerOasis, Inc. v. T-Mobile USA, Inc., 522 F.3d 1299 (Fed. Cir. 2008)

David Foster Wallace might have pointed out that the failure in PowerOasis, Inc. v. T-Mobile USA, Inc. stems from a failure to appreciate the bifurcated nature of time in patent law.

But, here is the context: PowerOasis held patents related to "vending machines" for telecommunications access—essentially the precursors to modern Wi-Fi hotspots found in airports and cafes. The patents claimed a system with a "customer interface" that allowed users to purchase access.

The Provisional/Priority Failure The patent family relied on an "Original Application" for priority. However, as the technology evolved, PowerOasis filed a Continuation-in-Part (CIP) application. In this CIP, they added significant new text to the specification. Specifically, they broadened the definition of "customer interface" to include software residing on the user's laptop, whereas the Original Application described the interface as being part of the vending machine kiosk itself.

PowerOasis sued T-Mobile, asserting that T-Mobile's Wi-Fi network infringed the patents. T-Mobile argued that their network, the "MobileStar" network, was already in public use more than one year before the CIP application was filed.

The court looked at the Provisional. It described a vending machine with a screen on the machine.

Then the court looked at the Non-Provisional (and the claims PowerOasis was asserting). These described a "customer interface" that could be on the user's laptop.

Because the Provisional did not describe the laptop interface, the claims were not entitled to the earlier date. The priority date slid forward. The MobileStar network, which existed in the gap, became invalidating prior art.

You cannot "fix" a thin provisional by adding definitions later.

You cannot "fix" a thin provisional by adding definitions later. When you add new text to cover a competitor's product, you are resetting the clock. You are creating a "Franken-patent" where different paragraphs have different birthdays, and usually, the one you need is too young to buy alcohol.

The Provisional Will Be Held Against You Problem

MPHJ Technology Investments, LLC v. Ricoh Americas Corp., 847 F.3d 1363 (Fed. Cir. 2017)

In this case, MPHJ owned a patent on a "virtual copier" system—software that allows a user to scan a document and drag-and-drop it into an application like email. The patent was asserting against major printer manufacturers.

The Provisional/Non-Provisional Discrepancy The provisional application described the invention as a "one-step" process. It contained specific definitions and language emphasizing the "seamless" and "single-step" nature of the operation. However, in the non-provisional application, the patentee deleted the "one-step" limitation and the restrictive definitions, presumably to broaden the scope of the patent to cover multi-step processes used by competitors (e.g., scan to server, then open email).

Ricoh challenged the patent in an Inter Partes Review (IPR), arguing anticipation by prior art (Xerox patents). MPHJ tried to argue for a claim construction that would avoid the prior art but still catch infringers.

The court and the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) looked to the provisional application to understand what the inventor originally possessed. The discrepancy between the "one-step" provisional and the broad non-provisional was damning. The deletion of the limiting language was viewed not as a valid broadening, but as evidence that the inventor originally conceived of a narrow invention. Ultimately, the court affirmed a claim construction that rendered the patent invalid based on the prior art.

The provisional application creates a permanent record of what the inventor "possessed" at the time of invention. Significant deviations or deletions in the non-provisional can be used by litigators to argue that the broader claims in the issued patent are either invalid for lack of written description or must be narrowly construed to the scope of the provisional to save their validity. You cannot "delete" your way to a broader invention if the foundation isn't there.

The International Problem

If you think American law is harsh, you should meet the Europeans. The European Patent Office (EPO) operates with a level of bureaucratic rigidity that would make a Vogon poetry reading seem like a casual open mic night.

In the U.S., we have a "grace period." If you screw up your provisional but publish a paper, you have a year to fix it. In Europe, there is no grace. Absolute Novelty is the rule.

The European Treatment

The EPO applies a strict standard for priority under Article 87 of the European Patent Convention (EPC). The test is whether the subject matter of the claim is "directly and unambiguously derivable" from the priority document (the U.S. provisional). This is often called the "Gold Standard" or "Strict Identity" test.

Imagine you file a U.S. Provisional (P1) describing a "copper gear."

Later, you file a European application claiming a "metal gear" (broadening the scope).

The EPO says your "metal gear" claim is too broad to get the P1 date. It gets today's date.

But P1 published 18 months ago.

P1 discloses a "copper gear." Copper is a metal.

Therefore, your own P1 document proves that your "metal gear" is not new.

Result: Your patent is invalid. You have collided with yourself.

This "self-collision" means that a "thin" provisional that discloses a specific example but fails to support the broad genus can act as a poison pill, killing the broader global patent rights.

The Chinese Treatment

Then there is China. In the case of the Jiecang patent (CN201720389490.8), the patentee made a classic mistake. They filed a U.S. Provisional first because they were in a hurry.

The Problem: The invention was made in China. Chinese law (Article 20) requires a "Secrecy Review" before filing abroad.

The Consequence: Because they filed in the U.S. first without asking permission, their Chinese patent was declared invalid.

Additionally, unlike the U.S., where applicants can fix some priority chain issues during prosecution, China is extremely rigid. If the priority document (provisional) does not contain the exact technical solution, priority is lost. Since China does not have the robust "continuation" practice of the U.S., losing priority often means the applicant faces their own intervening disclosures as invalidating prior art, with no mechanism for recovery.

Startups often rush to file a U.S. provisional to "get a date" before a trade show. If your R&D team is in Shenzhen, you might have a problem.

Commercial Risks of a Bad Provisional

The legal failures described above manifest as tangible commercial losses. For startups and investors, the "quality" of a provisional is a valuation metric.

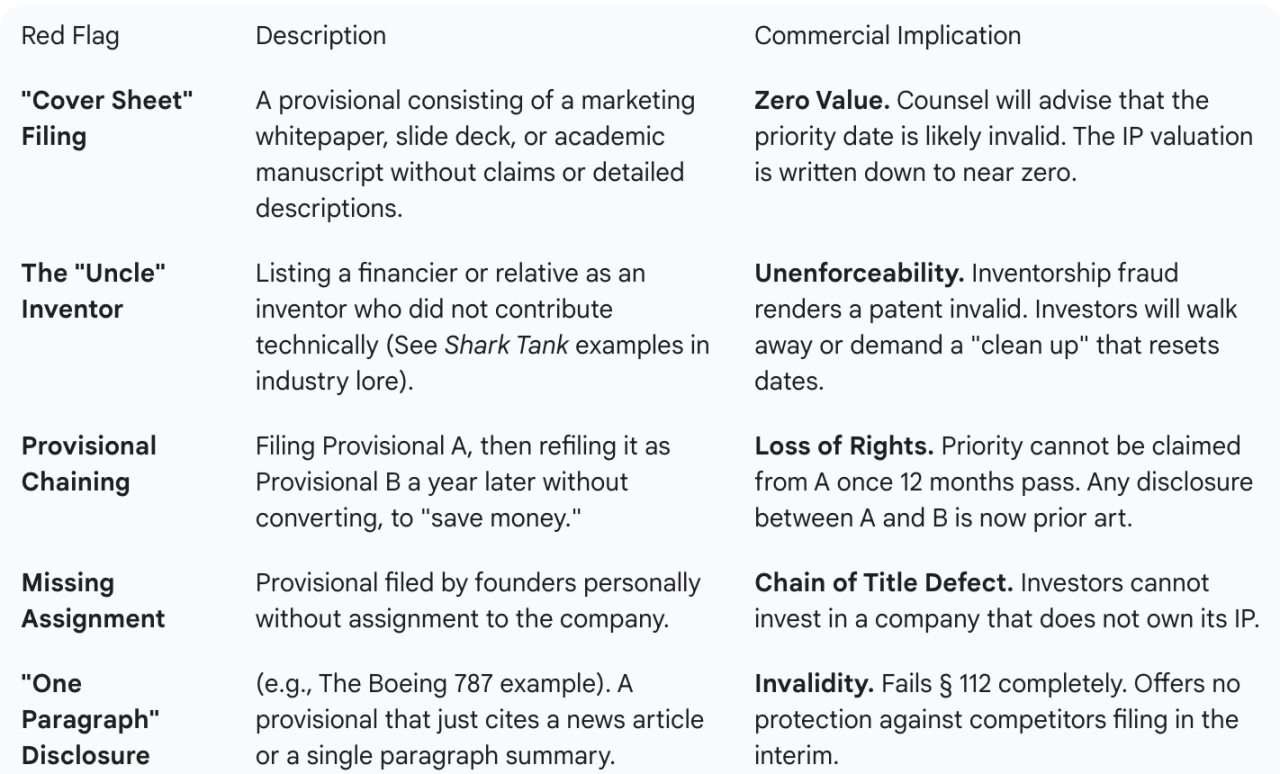

Due Diligence Red Flags: The Investor's Perspective

When Venture Capital (VC) firms or acquirers conduct due diligence, they employ IP counsel to audit the patent portfolio. A "thin" provisional is immediately flagged as a critical risk.

Investors know that a "thin" provisional is not a placeholder; it is a liability. It is a ticking time bomb that goes off exactly when you are trying to exit.

Don't Get Snookered

The ecosystem is plagued by predatory services offering "Patent Pending" status for nominal fees (e.g., $69 or $99).

These services often use automated forms that file a "provisional" consisting of whatever text the user types into a box. They rarely provide professional review for § 112 compliance.

The inventor receives an official USPTO filing receipt and believes they are protected. They then publicly disclose the invention.

When they later hire a real attorney, they learn the provisional is worthless. Because they disclosed the invention relying on the provisional, they have destroyed their own novelty rights. The "cheap" filing cost them the entire value of the invention.

Similar scams exist in trademark filing (as noted by the USPTO), where fraudulent entities file thousands of junk applications. The USPTO has begun sanctioning these entities, but the damage to the individual inventor is often irreversible.

Provisional Best Practices

To assist you in avoiding these fates, we have compiled a taxonomy of failure.

The Missing Detail: (See New Railhead). Include important details. If it's mechanical, draw it. Words are wind; drawings are evidence.

Don't Write a "Wish List": Describing what the invention does (e.g., "A drone that uses AI to avoid obstacles") without describing how (the specific algorithm). This fails Enablement.

Avoid Patent Profanity: Using words like "must," "always," "essential," or "critical." These words limit your scope. If you say the widget must be red, a competitor can steal your idea by making it blue.

Don't Describe a "Single Embodiment" Trap: Describing only the prototype on your desk. You must describe variations. "The casing is plastic, but could be metal, wood, or frozen tears."

Don't Use Ambiguous Terminology: Using words like "thin" or "strong" without defining them. "Thin" to a bridge builder is different than "thin" to a chip designer.

Don't Hide The "Best Mode": Hiding the secret sauce while asking for the monopoly. You cannot have it both ways.

The "One Paragraph" Provisional: Just don't.

Conclusion

Writing a patent application is not like writing a novel. In a novel, you can be ambiguous. You can leave things to the reader's imagination. You can trust that they will understand the subtext.

In patent law, subtext is death. Ambiguity is suicide.

If you are a startup, an inventor, or just a person with a bright idea, do not listen to the voice in your head that says, "It's just a provisional, we'll fix it later." That voice is a liar. That voice is trying to get you to walk into a propeller.

If you are a startup, an inventor, or just a person with a bright idea, do not listen to the voice in your head that says, "It's just a provisional, we'll fix it later." That voice is a liar. That voice is trying to get you to walk into a propeller.

Write it down. Draw it out. Describe the angle of the drill bit. Describe the algorithm. Describe the specific chemical composition of the glue. Do it now, while you still have the date.

Because once the clock ticks past midnight, the carriage turns back into a pumpkin, and the pumpkin is "Prior Art," and the Prince isn't coming to save you.

Footnotes

See 35 U.S.C. § 119(e)(1). The statute effectively says, "You get the date if you described it properly the first time." It’s a retrospective test. You don't know if your provisional is good until you try to use it, usually years later, when it's too late to fix it.

New Railhead Mfg., L.L.C. v. Vermeer Mfg. Co., 298 F.3d 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2002). A case that every mechanical engineer should have tattooed on the inside of their eyelids.

PowerOasis, Inc. v. T-Mobile USA, Inc., 522 F.3d 1299 (Fed. Cir. 2008). See also MPHJ Technology Investments, LLC v. Ricoh Americas Corp., where deleting a "one-step" limitation in the non-provisional backfired, proving the inventor originally had a narrow idea.

See EPO Enlarged Board of Appeal decisions regarding "Toxic Priority." It is a concept so Kafkaesque that it feels less like law and more like a punishment for hubris.

Re the Jiecang invalidation (CN201720389490.8). China’s Article 20 is strict. If you invent in China, you must file in China first (or ask permission). No exceptions for "I didn't know."

See "Project Matador" risk disclosures involving the interdependency of nuclear, gas, and battery systems. When billions are at stake, a $200 provisional is a structural failure point.

There is an apocryphal (but legally relevant) story of a provisional filed that was just a news article about the Boeing 787. It did not go well.

See "Patent Profanity" lists. Words like peculiar, supreme, and vital are the enemies of broad protection.