In the modern, knowledge-based economy, a curious phenomenon has taken root, one that challenges the foundational logic of intellectual property. Academics call it the "patent paradox": over the last few decades, the rate at which companies obtain patents for every dollar spent on research and development—what academics call "patent intensity"—has skyrocketed. Simultaneously, the expected value of any single, individual patent has appeared to decline.

This presents a direct and fascinating contradiction to the traditional theory of why patents exist. The classic justification, taught in law and business schools for generations, is that a patent grants a temporary monopoly, allowing a firm to appropriate the value of a specific invention by excluding others from using it. It is a legal shield, erected around a discrete innovation. If that is the case, and if the value of each shield is diminishing, why are rational, profit-maximizing companies acquiring them at an ever-accelerating rate?

The answer, which has profound implications for corporate strategy, competition, and innovation, is that the fundamental unit of analysis has changed. The strategic focus of modern patenting has shifted from the individual patent to the aggregated portfolio. This is the core of what Gideon Parchomovsky and R. Polk Wagner termed the "patent portfolio theory" Their crucial insight, now widely recognized in commercial practice, is that for patents, the whole is demonstrably greater than the sum of its parts. A portfolio of related patents creates synergistic value that a single patent cannot; it simultaneously increases both the scale and the diversity of marketplace protections.

This shift from the patent-as-unit to the patent-as-system has transformed intellectual property from a static legal function into a dynamic strategic one.It is no longer a terminal event but an ongoing process that begins at the moment of invention and does not end until the last patent in the portfolio expires. This evolution, however, is not a simple transition. It is a landscape defined by a series of powerful, often conflicting, tensions:

The Tension of Intent: The pull between patenting for pure protection versus patenting for strategic leverage—to block competitors, to use as bargaining chips, or to signal strength to investors.

The Tension of Value: The push and pull between accumulating a high quantity of patents to create a defensive thicket and cultivating a smaller portfolio of high-quality, high-impact patents.

The Tension of Alignment: The organizational friction between viewing the patent portfolio as a legal cost center managed for risk mitigation and viewing it as a strategic business asset managed for value creation.

The Tension of Time: The conflict between protecting the innovations of the past and the core business of the present, versus investing in the "blue-sky" intellectual property that will define the future.5

The Tension of Openness: The paradox of using an exclusionary tool (a patent) to enable collaboration and open innovation, acting as both a fence and a bridge.

Navigating these tensions is the essence of modern strategic patent portfolio management. It is a discipline that has moved from the legal department to the C-suite, demanding an integrated approach that bridges the traditional silos of engineering, law, and business. Understanding these dynamics is no longer optional; it is a critical capability for any company competing on the basis of innovation.

The Unit vs. The System: A New Theory of Value

The story of strategic patent management begins with a fundamental shift in perspective. For much of the 20th century, the patent was viewed through a singular lens: a legal instrument designed to solve the problem of appropriability. Innovation is expensive and risky; imitation is cheap and easy. Without a mechanism to prevent free-riders, the incentive to innovate would evaporate. The patent, by granting a temporary right to exclude, was the solution.6 In this model, the decision to patent was a relatively straightforward cost-benefit analysis centered on a single invention. Is the value of protecting this specific innovation from imitation greater than the considerable cost of obtaining and maintaining the patent?

This "unit-based" view, however, began to break down under the weight of empirical evidence. The patent paradox—more patents, less individual value—was the most glaring anomaly. The portfolio theory offered a new paradigm: the value of a patent is not solely derived from its own exclusionary power, but from its relationship to the other patents in a firm's portfolio.

A portfolio creates value in two primary ways: scale and diversity.

Scale refers to the sheer volume of patents in a related technological area. A single patent can often be "designed around" by a determined competitor who finds a slightly different way to achieve the same result. A dense portfolio of dozens or even hundreds of patents covering incremental variations, different applications, and alternative embodiments of a core technology creates what is often called a "patent thicket." Navigating this thicket becomes a daunting and expensive proposition for a competitor, who faces the risk of infringing on one of many patents, making it impractical to develop new products that avoid inadvertent infringement This creates a powerful deterrent effect that a single patent, no matter how strong, cannot replicate.

Diversity refers to the breadth of technological coverage within the portfolio. A diverse portfolio can protect not just a core product, but an entire user experience or business system. It can cover upstream components, downstream applications, and adjacent technologies. This diversity provides a much broader competitive moat. As Parchomovsky and Wagner noted, this aggregation of distinct-but-related patents provides a form of insurance; if one patent is invalidated in court or designed around, the others remain to provide protection.

This systemic view explains why a firm's patenting decisions are now often decoupled from the expected value of any single patent. The calculus is no longer about protecting one invention, but about building a strategic asset. This is why investors, particularly for early-stage companies, often look at the size and quality of a patent portfolio as a proxy for innovation and long-term viability, even before a product has significant market traction. The portfolio is a signal of strength, a tangible representation of a company's investment in its future competitive advantage.

The Tension of Intent: Protection vs. Strategy

The shift to a portfolio-centric view was not merely a change in tactics; it was driven by a fundamental expansion of strategic intent. The traditional motive for patenting—to protect an invention from imitation—is still relevant, but it has been joined by a host of other, more aggressive and nuanced strategic motives. This creates the first and most critical tension in portfolio management: the push and pull between building a portfolio for pure protection versus building one for strategic leverage.

A seminal 2007 study by Blind, Cremers, and Mueller provided clear empirical evidence of this dynamic. They analyzed the patenting motives of over 400 German companies and correlated those motives with the measurable characteristics of their patent portfolios.8 Their work gives us a powerful framework for understanding the different "jobs" a patent portfolio can be hired to do.

The Protection Motive: Building the Crown Jewels

The traditional motive, which the study labels the protection objective, is focused on securing a core innovation from being copied. When this is a firm's primary goal, it invests heavily in obtaining a few, high-quality patents with broad, defensible claims. The study found a clear and significant correlation: the more a company's patenting is driven by the protection motive, the higher the average number of citations its patents receive.8

Patent citations are a critical, if imperfect, proxy for a patent's value and technological significance.9 Pioneering research by scholars like Manuel Trajtenberg demonstrated that while raw patent counts are poor indicators of value, citation-weighted counts show a strong correlation with the social and economic welfare created by an innovation.9 A patent that is frequently cited by later inventions is likely a foundational piece of technology—one that stands on the "shoulders of giants," to borrow Suzanne Scotchmer's famous phrase.11 Therefore, a portfolio built for protection is, by its nature, a collection of "crown jewel" patents. Each one is intended to be a strong, valuable asset in its own right.

Strategic Motives: Building the Wall and the Bargaining Chips

In contrast to the protection motive, the study identified several strategic motives that have become increasingly prevalent. These are not about protecting a single invention, but about shaping the competitive landscape.

Offensive Blocking: This involves patenting not just your own innovations, but also adjacent technologies that a competitor might need for their own R&D path. The goal is to create roadblocks and increase the cost of innovation for rivals. The study found that portfolios dominated by this motive receive significantly fewer citations on average. This is not an accident; it is a feature of the strategy. The firm is deliberately accumulating patents of lower individual value to create a dense thicket, making it difficult for competitors to operate without infringing. This strategy also comes with a cost: the study found that an offensive blocking strategy is correlated with a higher incidence of patent oppositions, as competitors recognize the aggressive posture and fight back.

Defensive Blocking: This is a more reactive strategy, aimed at preserving a company's own freedom to operate. By patenting incremental improvements and variations around its own technology, a firm can prevent competitors from patenting those same variations and then using them to sue the original innovator. The study found this motive to be closely related to the traditional protection motive, suggesting it is a forward-looking form of defense.

Exchange (Bargaining Chips): In complex technology sectors like semiconductors and telecommunications, where products are composed of hundreds or thousands of patented inventions, it is virtually impossible to build a product without infringing on someone else's patents. This has led to the rise of large-scale cross-licensing agreements, where companies grant each other access to their respective portfolios. In this environment, patents become bargaining chips. A large portfolio, even if composed of individually less valuable patents, provides leverage in these negotiations. The study confirmed this, finding that portfolios built for the exchange motive also receive fewer citations.8 Interestingly, they also receive fewer oppositions, suggesting that firms engaged in these collaborative ecosystems prefer to avoid conflict and resolve disputes informally.

This research illuminates the central tension of intent. A company cannot simultaneously optimize for all motives. A strategy focused on creating a few, high-value "crown jewel" patents for pure protection is fundamentally different from a strategy focused on creating a high-volume "patent thicket" for offensive blocking or exchange. The former prioritizes individual patent quality (as measured by citations), while the latter prioritizes portfolio quantity and density.

This tension forces a critical strategic choice. Is the goal to have the single strongest patent in a legal battle, or to have a wall of 100 patents that makes a legal battle too costly for a competitor to even consider? The answer depends entirely on the company's business model, its competitive environment, and its long-term strategic objectives. The failure to consciously make this choice is one of the most common pitfalls in portfolio management, leading to a collection of patents that is neither a strong shield nor an effective strategic weapon—it is simply an expensive hobby.

The Managerial Tension: Cost Center vs. Value Driver

The expansion of patenting from a purely protective legal function to a complex strategic one has created a significant tension within the modern corporation. Historically, the intellectual property department was a legal cost center. Its job was to file patents and manage risk, and its budget was an expense to be minimized. Today, however, a well-managed patent portfolio is recognized as a primary driver of corporate value, capable of attracting investors, influencing M&A valuations, generating licensing revenue, and serving as collateral for financing.

This creates a fundamental push-and-pull dynamic between the legal and business functions of a company. The legal team, trained in risk mitigation, often defaults to a defensive posture. The business team, focused on growth and ROI, needs the IP portfolio to be an offensive tool. This disconnect is often a source of immense friction and missed opportunity. As William Fisher III noted in the California Management Review, engineers, lawyers, and business executives often lack a common framework and language to develop an integrated approach to IP and firm strategy. Lawyers are often brought in too late, after a product is already developed, and are forced to say "no" rather than being able to shape the product's design to reflect legal opportunities from the start.

Resolving this tension requires elevating patent management from a siloed legal task to a core, cross-functional strategic process. Success is rooted in a triad of a clear strategy, a supportive organization, and sophisticated core processes. A brilliant strategy is useless if the organization is not structured to implement it.

This means creating a culture and a set of processes where the patent strategy is not an afterthought, but is derived directly from the corporate vision and mission. It requires a continuous dialogue between the C-suite, R&D, and legal counsel to ensure that every decision—from which inventions to patent, to which jurisdictions to file in, to which patents to maintain or abandon—is aligned with the company's overarching business goals.

The companies that manage this tension effectively are the ones that treat their patent portfolio not as a collection of legal documents, but as a dynamic business tool. They understand that the true value of the portfolio comes from how it is managed and integrated into broader business strategies. This requires a new set of frameworks for thinking about and managing intellectual property.

Frameworks for Navigating the Tensions

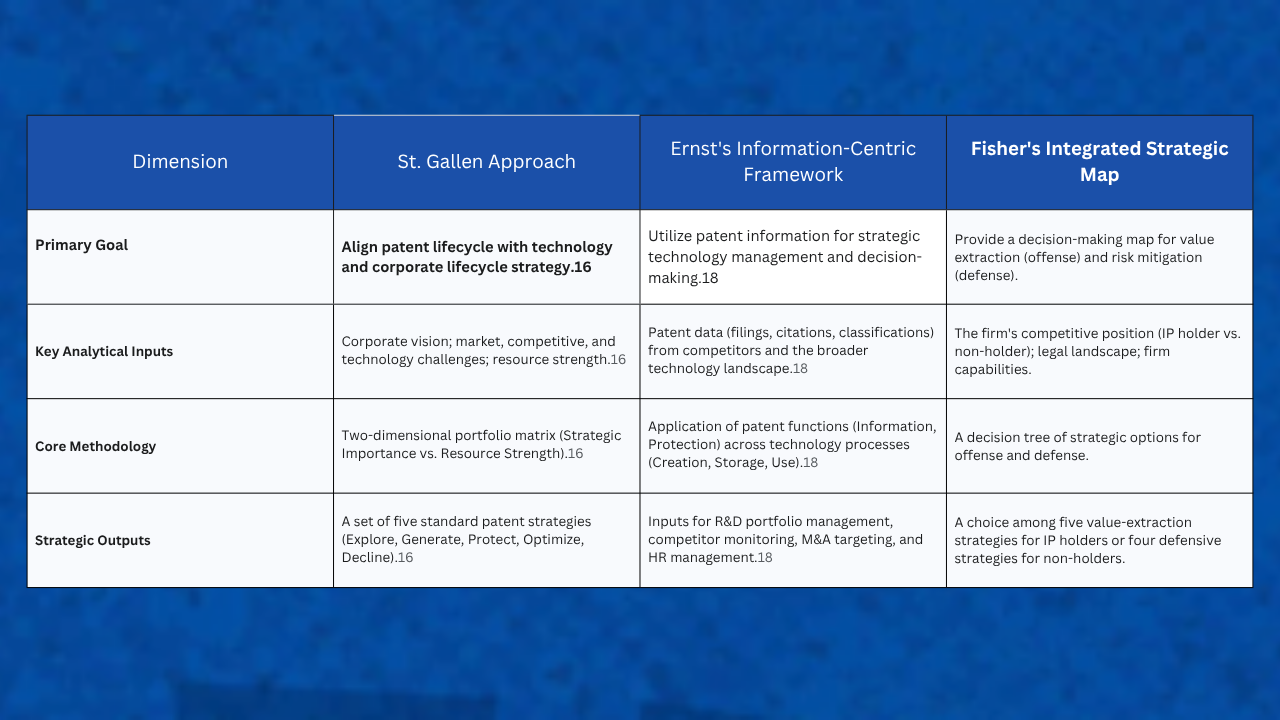

The academic literature provides several powerful conceptual frameworks that can help managers bridge the gap between legal detail and business strategy. These are not rigid, prescriptive models, but rather strategic lenses that can help clarify the trade-offs and guide decision-making. Three of the most influential are the St. Gallen approach, Ernst's information-centric framework, and Fisher's integrated strategic map.

The St. Gallen Approach: The Lifecycle Lens

Developed at the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland, this framework provides a rigorous, top-down methodology for aligning the patent lifecycle with the technology and corporate lifecycle. The process begins with the company's vision and mission and assesses the technological challenges from the perspective of customers, competitors, and potential substitute technologies.

The core of the framework is a two-dimensional "Technology Portfolio" matrix. It maps the company's technological competencies based on their Strategic Importance and the Relative Strength of the company's resources in that area. This analysis yields five standard technology strategies, which directly correspond to a typical product lifecycle:

Observe: For emerging technologies of low current importance.

Study: For technologies of growing importance where the company is building initial competence.

Invest: For core technologies with high strategic importance and strong internal resources.

Optimize: For mature technologies where the focus is on ROI, not further investment.

Divest: For declining technologies with no foreseeable competitive advantage.

From this technology portfolio, a corresponding "Patent Portfolio" with five parallel strategies is derived: Explore, Generate, Protect, Optimize, and Decline. Each phase dictates specific patenting actions. In the "Explore" phase, the company might conduct broad patent searches and file patents with wide claims on promising new concepts. In the "Protect" phase for core technologies, the focus shifts to filing patents with broad claims, monitoring major competitors, and defining a global protection strategy. In the "Decline" phase, patents are reviewed for abandonment or sale to cut costs.

The power of the St. Gallen approach is its explicit linking of patent activity to the strategic lifecycle of the business. It provides a clear answer to the tension of time: it forces managers to think about which technologies are in the past (Decline), which are the present (Protect/Optimize), and which are the future (Explore/Generate), and to allocate patent resources accordingly.

Ernst's Information-Centric Framework: The Data Lens

Holger Ernst's framework, developed in 2003, reframes the patent system itself. It argues that patents serve two primary functions: Information and Protection. These functions are then applied across the three core processes of technology management: Creation, Storage, and Use.

This framework highlights the often-underutilized value of patents as a source of competitive intelligence. For example:

In Technology Creation, the information function of patents is used to monitor competitors' R&D strategies, assess the technological landscape, and identify potential M&A targets or alliance partners.18 Analyzing patent filing trends can provide crucial insights into a competitor's future plans long before a product is launched.

In Technology Use, the protection function is used not only to protect products from imitation but also to gain strategic advantages through cross-licensing or patent sales.

Ernst's framework is particularly relevant in the modern era of big data. It positions patent analytics not as a niche legal task, but as a central competitive intelligence function that should inform R&D portfolio management, M&A strategy, and even human resource management (by identifying key inventors at competing firms).It provides a powerful argument for transforming the patent department from a cost center into an intelligence hub.

Fisher's Integrated Strategic Map: The Game Theory Lens

William Fisher's framework, published in the California Management Review, provides a practical decision-making "map" for both offensive and defensive IP strategy. It is explicitly designed to facilitate the crucial conversation between managers, lawyers, and innovators.

For IP Holders (Offense), the framework challenges the default assumption that the best strategy is always to suppress competition. It outlines five distinct ways to extract value from an IP right:

Exercising Market Power: The traditional exclusion model.

Selling the IP Right: Assigning the patent to another firm where it might be more valuable.

Licensing the Right: Granting permission to others, including competitors, to use the IP in exchange for royalties.

Organizing Collaborations: Using the IP as a basis for joint ventures or other partnerships.

Giving the Right Away: Waiving the right, for example, to help establish a technology as an industry standard.

For Firms Lacking IP (Defense), the map presents alternatives to costly litigation:

Developing a Non-Infringing Alternative: Inventing around the competitor's patent.

Securing a License: Paying for the right to use the technology.

Building a Defensive Portfolio: Accumulating patents to deter litigation through the threat of a countersuit (mutually assured destruction).

Deploying Rapidly: Launching a potentially infringing product so quickly and widely that it creates a new market reality, making it difficult for a court or the IP holder to unwind.

Fisher's framework excels at highlighting the strategic trade-offs. It forces a company to move beyond a simplistic "sue or be sued" mentality and consider a much richer set of strategic options. It directly addresses the tension between value capture (taking a larger slice of the pie) and value creation (making the pie bigger for everyone), noting that an aggressive focus on the former can often be detrimental.

These frameworks, while different, all point to the same conclusion: strategic patent management is an active, not a passive, discipline. It requires a system.

The Operational Tension: Accumulation vs. Optimization

A patent portfolio is not a static collection of trophies to be displayed in a cabinet. It is a dynamic, living asset that requires constant attention, curation, and management. This creates another fundamental tension: the pull between the desire to accumulate more assets (to build a bigger portfolio) and the need to optimize the existing portfolio for cost, relevance, and strategic alignment.

Patents are expensive. Filing fees, attorney fees, and ongoing maintenance fees (annuities) can add up to tens of thousands of dollars per patent over its lifetime, especially for international protection.4 A large portfolio can represent millions of dollars in annual costs. This financial reality makes the active management of the portfolio not just a best practice, but a financial necessity.

The Portfolio Audit: Confronting Reality

The cornerstone of portfolio optimization is the regular portfolio audit. This is a systematic review, often conducted on a 3-5 year cycle to align with business strategy reviews, that assesses each patent against current business objectives.5 The audit is not just about checking if a patent is still legally valid; it is about asking hard strategic questions:

Is this patent still protecting a core product or revenue stream?

Does this patent align with our current R&D priorities and product roadmap?

Has the technology covered by this patent become obsolete?

Are maintenance fees justified by the patent's current business priority?

Can competitors easily design around the claims, rendering the patent ineffective?

The audit process forces a company to confront the tension between the past and the present. It often reveals that a significant portion of the patent budget is being spent to maintain patents related to defunct or shrinking product lines, while core, growing business lines may be under-protected.

Strategic Abandonment: The Power of Pruning

The most important outcome of a portfolio audit is the identification of assets for strategic abandonment, or "pruning" This is the process of deliberately allowing patents that no longer serve a strategic purpose to lapse by not paying maintenance fees.

This can be a culturally difficult process. Companies, and the inventors within them, often become emotionally attached to their patents. Abandoning one can feel like admitting failure. However, from a strategic perspective, pruning is one of the most powerful levers for optimization. Every dollar spent maintaining a legacy patent is a dollar that cannot be invested in filing a new patent for an emerging technology By "cutting the dead weight," a company can reallocate its finite IP budget from protecting the past to investing in the future.

For assets that are no longer core to the business but may still have value to others, divestment through a patent sale is another viable option. This can turn a cost center into a one-time revenue generator, providing capital that can be reinvested into the core business. The tension between accumulation and optimization is perpetual. The natural inclination is often to file more patents and grow the portfolio. However, the most strategically mature companies understand that managing the outflow of assets through disciplined pruning is just as important as managing the inflow of new filings. A lean, highly-aligned portfolio is almost always more valuable than a large, bloated, and unfocused one.

The Ecosystem Tension: Fences vs. Bridges

The traditional view of patents is that they are fences, designed to exclude. This view, however, is increasingly incomplete in a world defined by open innovation, digital ecosystems, and complex collaborations.24 This gives rise to one of the most subtle and important tensions in modern IP strategy: the dual role of patents as both fences that protect and bridges that connect.

Initially, the exclusionary nature of patents was seen as being in direct conflict with the collaborative principles of open innovation.24 If innovation requires the free flow of ideas across organizational boundaries, how can a legal tool designed to stop that flow be anything but an impediment?

The scholarly literature, however, has developed a more nuanced perspective. Far from hindering open innovation, patents are now understood to be crucial instruments for governing and enabling it. The theory of "good fences make good neighbors" is particularly apt here. In a collaborative R&D project, patents can clearly delineate the technological boundaries and ownership of each party's contributions. This clarity reduces the risk of future disputes and creates the trust necessary for open exchange.

In this context, patents are not just about appropriation; they are about facilitating a "market for know-how". A company with a strong patent position can more confidently engage with external partners, knowing that its core technology is secure. This allows it to license its technology to others, enter into joint ventures, and acquire technology from startups, using its IP portfolio as a key strategic asset in these transactions. Empirical research has even shown that firms engaged in open innovation have stronger motives to patent than those with closed innovation models.

This dual role creates a delicate balancing act. The firm must maintain control over its proprietary technology (the fence) while simultaneously fostering an environment that encourages the open exchange of ideas (the bridge). This requires sophisticated IP management, particularly through comprehensive collaboration agreements that clearly define ownership, usage rights, and commercialization plans from the outset.

The tension between patents as fences and patents as bridges is at the heart of strategy in modern digital ecosystems. These ecosystems are not vertically integrated hierarchies, but networks of interconnected stakeholders—partners, suppliers, customers, and even competitors—that collaborate to create value. In such an environment, a purely defensive, exclusionary IP strategy is often suboptimal. The most successful firms are those that learn to use their patent portfolios not just to build walls, but to build bridges that connect them to the broader innovation landscape.

The Future Tension: Human Intuition vs. AI Augmentation

The final, and perhaps most transformative, tension is the one that is only now beginning to take shape: the interplay between traditional, experience-based human strategy and the emerging power of data-driven, AI-augmented decision-making. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is being described as a "game-changer" that is fundamentally reshaping the practice of patent portfolio management.

For decades, patent strategy has been the domain of human experts—seasoned patent attorneys and business leaders who relied on their experience, intuition, and manual analysis to make strategic decisions. This is rapidly changing. The exponential growth in global patent data—with millions of new applications filed each year—has made manual analysis insufficient. AI-driven tools are now capable of processing and analyzing these vast datasets at a scale and speed that is impossible for humans.

The impact of AI can be seen across three layers:

Operational Efficiency: AI is automating time-consuming tasks like prior art searches, patent landscape analysis, and competitor monitoring, making these processes faster, cheaper, and more accurate.

Process Enhancement: AI is augmenting core strategic processes. For example, AI-powered patent valuation tools can analyze factors like citation frequency, market trends, and litigation history to automatically score the patents in a portfolio. This provides a quantitative, data-driven input for the portfolio audit and pruning decisions discussed earlier, reducing human bias and enabling more scalable and consistent evaluation.

Strategy Enablement: Most profoundly, AI is enabling entirely new strategic capabilities. Predictive analytics algorithms can analyze historical data to forecast the future value of a patent, predict the likelihood of a patent application being granted, and identify technological "white space" where there are opportunities for new innovation.

This creates a new tension between the old way and the new way. The traditional approach to strategy is reactive: a company invents something, and the patent department protects it. The new, AI-enabled approach is proactive and predictive. By analyzing trends in patent filings, scientific literature, and venture funding, AI systems can help a company anticipate where a technology field is heading and strategically file patents in that area before the innovation has even been fully developed.

This does not mean that human expertise will become obsolete. The role of the strategist will shift from conducting manual analysis to interpreting the outputs of AI systems, asking the right questions, and making the final, nuanced judgments that machines cannot. The tension will be in finding the right balance—leveraging the scale and predictive power of AI while retaining the crucial context, creativity, and strategic wisdom of human experts. The firms that master this human-AI collaboration will have a significant competitive advantage, as they will be able to make faster, more informed, and more forward-looking decisions about their most valuable assets.

Conclusion: The Unwinnable Game and Why You Must Play It

The strategic management of patent portfolios is not a problem to be solved, but a series of tensions to be continuously managed. There is no single "right" answer to the question of whether to prioritize quality or quantity, offense or defense, the past or the future, fences or bridges. The optimal strategy is contingent on a company's specific industry, competitive position, and corporate objectives.

What is clear, however, is that the failure to actively and strategically manage these tensions is a recipe for failure. A patent portfolio that is not aligned with business goals is a costly and ineffective asset. It consumes resources without providing a competitive moat, generating revenue, or increasing shareholder value.

The evolution from the patent-as-unit to the patent-as-system has permanently changed the game. The companies that will win in the knowledge economy are not necessarily those with the single best invention, but those with the most coherent and well-managed portfolio strategy. They are the ones that have elevated IP management from a back-office legal function to a core strategic discipline. They have built the organizational structures and processes to foster a continuous dialogue between their legal, technical, and business teams. They have adopted formal frameworks to guide their decision-making, and they are embracing new technologies like AI to make those decisions faster and smarter.

The push and pull between competing strategic imperatives will never go away. The landscape of technology, competition, and law is in constant flux. The challenge for every innovative company is to not seek a final, static solution, but to build the organizational capability to navigate these tensions with agility, foresight, and strategic intent. In the end, a patent portfolio is a reflection of a company's strategy—or lack thereof. The ones that are built with purpose will be the ones that endure.

Works cited

Patent Portfolios - Penn Carey Law: Legal Scholarship Repository, accessed October 7, 2025,

Using Patent Portfolio to Effectively Manage Technical Assets: The Mechanism of Patent Portfolio to Influence Firm Performance - SciTePress, accessed October 7, 2025,

(PDF) Patents as Indicators for Strategic Management - ResearchGate, accessed October 7, 2025

Patent Portfolio Management: Strategy, Value & Best Practices - The National Law Review, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent Portfolio Management: A Penny Saved is a Penny Earned | Miller Nash LLP, accessed October 7, 2025,

A Study on Patent Strategy and Management, accessed October 7, 2025,

The Impact of Patent Portfolio Diversity on Firm Performance in Digital Enterprises—The Moderating Role of Regional Digital Economy Development Levels - ResearchGate, accessed October 7, 2025,

The Influence of Strategic Patenting on Companies' Patent ... - ZEW, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent research in academic literature. Landscape and trends with a focus on patent analytics - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent research in academic literature. Landscape and trends with a focus on patent analytics - Frontiers, accessed October 7, 2025,

How do patents affect research investments? - PMC, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent management: the prominent role of strategy and organization - Emerald Publishing, accessed October 7, 2025,

Maximizing IP Value: A Guide to Strategic Patent Portfolio Management - Patentskart, accessed October 7, 2025,

IP Rationalization: Making Portfolio Decisions Aligned with Growth | PatentPC, accessed October 7, 2025,

Intellectual Property as a Strategy for Business Development - MDPI, accessed October 7, 2025

(PDF) Strategic Management Of Patent Portfolios - ResearchGate, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent portfolio management: literature review and a proposed model, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent information for strategic technology ... - LexisNexis IP, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent Landscape Analysis: Actionable Insights for Strategic Decision Making - UnitedLex, accessed October 7, 2025,

Strategic Management of Intellectual Property - Harvard Business ..., accessed October 7, 2025,

5 tips for managing your patent portfolio - IP Insights - Wilson Gunn, accessed October 7, 2025

Optimize Patent Portfolio with Strategic Abandonment - TT Consultants, accessed October 7, 2025,

Portfolio Optimization: Best-Practices Strategies to Maximize Value - UnitedLex, accessed October 7, 2025,

Value capture in open innovation markets: the role of patent rights for innovation appropriation - Emerald Publishing, accessed October 7, 2025,

Strategic Management of Open Innovation: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective, accessed October 7, 2025,

(PDF) Intellectual Property Management in Open Innovation - ResearchGate, accessed October 7, 2025,

Comparing Business, Innovation, and Platform Ecosystems: A Systematic Review of the Literature - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed October 7, 2025,

Interfacing Intellectual property rights and Open innovation - WIPO, accessed October 7, 2025.

Patents and Open Innovation: Bad Fences Do Not Make Good Neighbors | Cairn.info, accessed October 7, 2025,

IP Strategy: How Patent Portfolios Can Secure Powerful Partnerships - Caldwell Law, accessed October 7, 2025,

Exploring the digital innovation ecosystem from the perspective of platform-based startups: a case study in the film industry - Emerald Insight, accessed October 7, 2025,

AI-driven Patent Portfolio Analysis - Effectual Services, accessed October 7, 2025,

The Future of Patent Portfolio Management: Trends and Innovations - PatentPC, accessed October 7, 2025,

AI-Driven Patent Portfolio Management: Maximizing ROI in Innovation - Patentskart, accessed October 7, 2025,

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Patent Lifecycle Management, accessed October 7, 2025.

Artificial Intelligence in Patent and Market Intelligence: A New Paradigm for Technology Scouting - arXiv, accessed October 7, 2025.

The Impact of AI on Patent Portfolio Management - Patent PC, accessed October 7, 2025,

Top 5 Mistakes by In-House Patent Counsel – And How to Avoid Them - KPPB LAW, accessed October 7, 2025,