Patents have long been a double-edged sword in the startup world. On one hand, a patent can confer a temporary monopoly and signal technological prowess; on the other hand, the patent process is costly, slow, and public.

Founders often hear mixed advice: some investors dismiss patents as mere “checkboxes,” while others insist that strong intellectual property (IP) is crucial for attracting venture capital or acquirers.

So what strategic role do patents actually play in a startup’s growth and financing prospects?

Recent empirical research provides data-driven insights into when and how patents contribute to startup success. Overall, the evidence shows that patents can boost a startup’s fundraising, valuations, and exit opportunities – but their impact varies widely by industry, timing, and context, and they are neither necessary nor sufficient for success (Patent Strategies of Technology Startups An Empirical Study).

In this article, we dive into scholarly findings to offer an analytical, advisory perspective for founders on leveraging patents as a strategic asset (or deciding not to), and how to balance the benefits against the costs in the early stages of venture formation. Here are the primary sources we use:

Patent Strategies of Technology Startups An Empirical Study (Lerman, 2015)

What is a Patent Worth - Evidence from the US Patent Lottery (Farre-Mensa, et al, 2017)

Small Firms, Big Patents? Estimating Patent Value Using Data on Israeli Start-ups’ Financing Rounds (Greenberg, 2013)

Resources as Dual Sources of Advantage: Implications for Valuing Entrepreneurial-Firm Patents (Hsu and Ziedonis, 2013)

Patents as Signals in Fundraising and Growth

One of the clearest findings in the literature is that startups with patents tend to have better outcomes in financing. Patents serve as signals of innovation quality and as legal assets that investors can get behind. A comprehensive study by Celia Lerman examined thousands of U.S. tech startups and found a “significant positive relationship” between patenting and the ability to raise investment funds (Patent Strategies of Technology Startups An Empirical Study).

Not only were venture-backed startups more likely to patent than those without venture funding, but each additional patent was associated with higher total funding raised. This runs contrary to the anecdotal belief that investors only care if you have a patent versus none – in fact, Lerman’s data indicated that having more patents can translate to more capital, potentially because multiple patents reinforce the signal that a company has valuable technology (Patent Strategies of Technology Startups An Empirical Study.pdf).

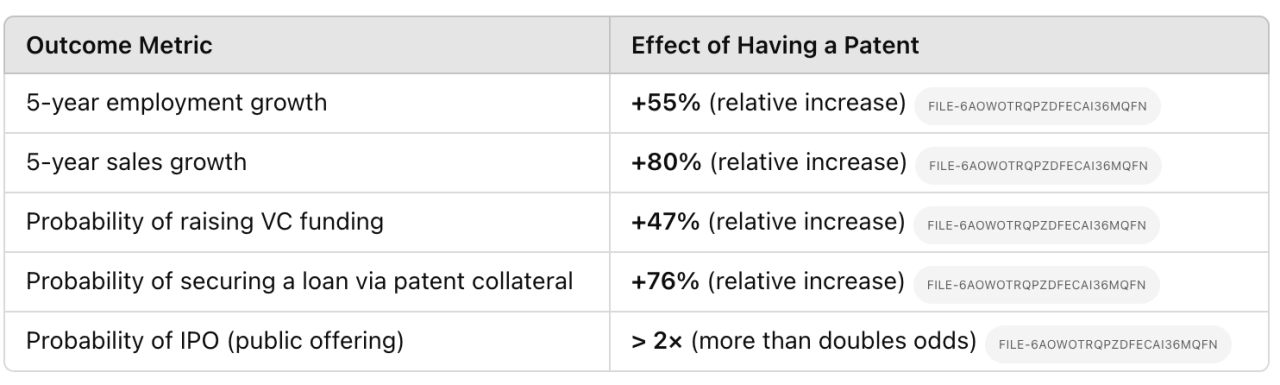

Academic studies have attempted to quantify how much a patent influences funding and growth. A particularly compelling approach comes from a study nicknamed the “patent lottery,” which exploited the quasi-random assignment of patent examiners to startup patent applications (What is a Patent Worth - Evidence from the US Patent Lottery). In this study, startups that “won” the lottery by getting a lenient examiner (and thus secured a patent grant) were compared to similar startups that narrowly missed getting a patent. The results were striking: obtaining that first patent caused startups to grow 55% faster in employment and 80% faster in sales over the next five years (What is a Patent Worth - Evidence from the US Patent Lottery). Moreover, the patent-holding startups were far more successful in securing financing. Table 1 summarizes some of the key impacts identified:

Table 1: Estimated impact of obtaining a patent on startup outcomes (U.S. Patent “Lottery” study)

Outcome Metric Effect of Having a Patent 5-year employment growth +55% (relative increase) 5-year sales growth +80% (relative increase) Probability of raising VC funding +47% (relative increase) Probability of securing a loan via patent collateral +76% (relative increase) Probability of IPO (public offering) > 2× (more than doubles odds)

These are huge differences. A patent grant increased the likelihood of securing venture capital by nearly 50%, and even more dramatically improved access to other funding avenues like bank loans (by 76%, since patents can be pledged as collateral). Perhaps most eye-opening, patenting more than doubled the chances of a successful exit via IPO ( Why do patents have such an outsized effect on financing? The researchers found that patents help overcome information frictions: they give investors a tangible asset and legal recourse (in case of IP disputes or expropriation) and signal that the startup’s technology has merit vetted by an external institution (the patent office).

This effect was strongest in situations with high uncertainty – for example, patents provided the biggest boost for startups that had not already raised significant funding, for first-time or inexperienced founders, and for companies outside major startup hubs where investor attention is harder to get (What is a Patent Worth - Evidence from the US Patent Lottery). In other words, patents act as a credibility booster when other credibility markers (like prior investor backing or famous founders) are absent.

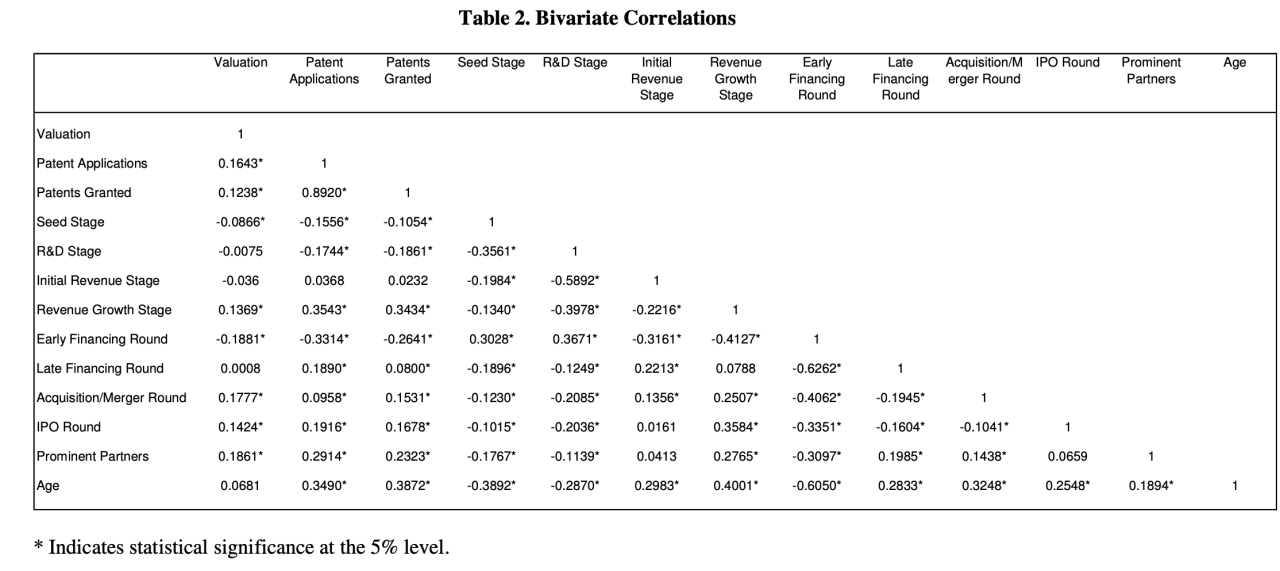

Multiple studies corroborate that patents serve as positive signals to venture capitalists. An analysis of Israeli startups found that simply having patent applications on file was associated with significantly higher company valuations (Small Firms, Big Patents? Estimating Patent Value Using Data on Israeli Start-ups’ Financing Rounds). Each additional patent application corresponded to roughly a 45% increase in valuation in subsequent financing rounds, according to that study. Interestingly, once a patent was granted, valuations got an extra bump – an estimated 28% additional increase for young startups in early funding rounds.

This suggests that while just filing for a patent already signals value, the uncertainty resolution that comes with an issued patent provides even more assurance to investors, particularly for early-stage companies. Consistent with this, prior research on U.S. ventures (Hsu and Ziedonis, 2008) showed that doubling a startup’s patent stock was associated with a 28% higher pre-money valuation in VC deals, and that patents’ signaling value was most pronounced in earlier rounds. Another study of software startups in the late 1990s found that those with patents secured more financing rounds and greater total investment than those without, though the sheer number of patents didn’t matter as much in that particular sample. The qualitative consensus is clear: venture investors do pay attention to patents as one indicator of a startup’s potential.

That said, not all patents are created equal in investors’ eyes. Some venture capitalists frankly admit that patents can be a superficial checkbox – they want to see you have something, but they may not scrutinize the details (Lerman 2015). In an interview study, one VC remarked that “patents are a checkbox in the investor list,” and that while investors ask whether a company has patents, they rarely dig deeply into patent quality (Lerman, 2015). Empirically, there is evidence that patent quality or relevance matters: one survey of 351 startup executives found that having patents per se did not boost valuations unless the patents were considered “useful” to the business – in fact, startups with useless patents fared worse, presumably because they wasted resources on IP that didn’t help their prospects (Greenberg, 2013). This reinforces an important point for founders: a patent portfolio’s value lies in its substance, not just its existence. A few strong patents protecting your core innovation are far more valuable than a stack of irrelevant or low-quality filings. Still, the signal of having at least one patent appears to be meaningful – Lerman’s study noted that most companies tend to secure their first patent even before raising any funding, highlighting that savvy founders use early patent filings to signal their startup’s potential (Lerman, 2018).

Patents and Exit Opportunities (Acquisitions and IPOs)

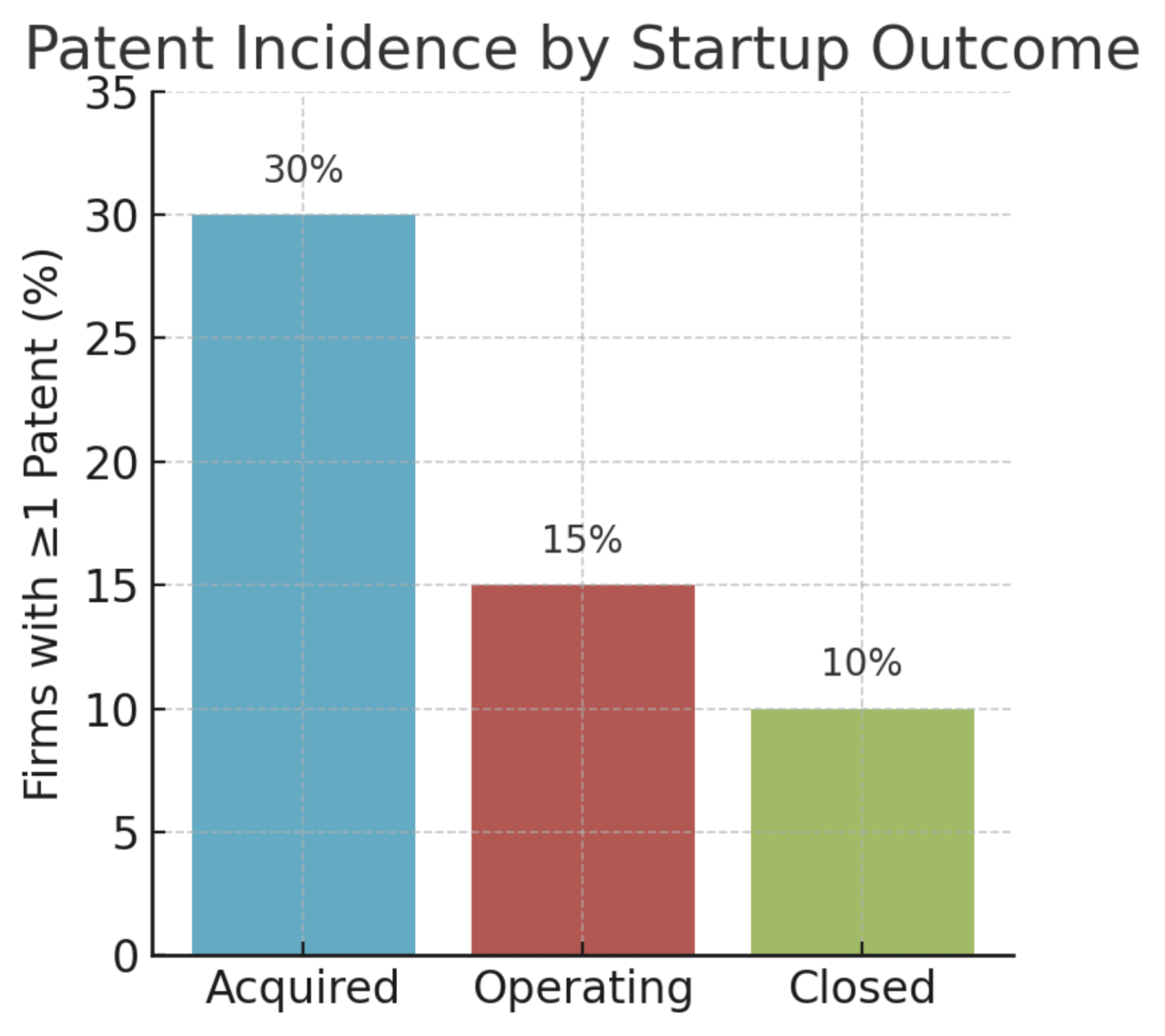

Beyond fundraising, patents also play a strategic role in startup exit outcomes. Many startup acquisitions – especially in the tech and biotech sectors – are essentially IP acquisitions in disguise. A larger company may be less interested in the startup’s short-term revenues than in its patented technology, which can be integrated into the acquirer’s products or used defensively to protect a market position. Data backs up this intuition: acquired startups have significantly more patents than those that remain independent or shut down.

In Lerman’s analysis, a startup that achieved an acquisition was almost twice as likely to have at least one patent as a still-operating (private) startup, and almost three times as likely as a failed startup that closed its doors (Lerman, 2018). Put differently, the companies that got acquired were disproportionately those with patented innovations, whereas the pool of failed startups is full of companies that never patented anything. This doesn’t prove that patents cause acquisitions, but it underscores that patenting is closely correlated with desirable exit events. It stands to reason that innovative companies will both patent more and attract acquirers – but having the patents likely helps the acquiring company justify the purchase price (and in some cases, the presence of IP can trigger bidding wars among potential buyers).

Figure: Share of startups with at least one patent, by eventual outcome. Studies find that successful startups (those acquired by another company or going public) are far more likely to have patented technology, whereas failed startups are much less likely to hold any patents (Illustrative data based on Lerman’s 2015 study.)

Patents can also directly increase the valuation of an exit. If a startup IPOs, a strong patent portfolio can boost investor confidence in its long-term competitive advantage, potentially leading to a higher IPO pricing. And in acquisitions, patents can add explicit value – either by enabling freedom to operate (for the acquirer) or by offering licensing opportunities. There have been prominent examples of “acqui-hire” deals where patents were a key asset; for instance, large tech companies have bought smaller startups primarily to obtain their patent rights (sometimes to bolster a defensive arsenal in patent litigation-heavy industries).

The “patent lottery” study from above also connected patents to exit outcomes: it found that having a patent doubled the odds of a startup eventually going public (What is a Patent Worth - Evidence from the US Patent Lottery). This suggests that patents not only help startups survive and grow to reach the IPO stage, but also that public market investors value patent-protected innovation. For acquisitions, while we don’t have a randomized experiment, the strong correlations indicate patents make a startup a more attractive target. The rationale is straightforward – a startup with no patents might be cheaper to copy than to buy, whereas a patented technology forces a potential competitor to either license, litigate, or acquire. From an acquirer’s perspective, buying the company outright (along with its IP) can eliminate future competition and secure a technological edge. Thus, patents serve as a form of leverage in exit negotiations.

However, founders should also be aware that patents are not the only path to a good exit. Many successful startups have been acquired or gone public without significant IP portfolios, especially in sectors like software or consumer internet where speed of execution or network effects matter more than patented tech. In those cases, other assets (user base, data, talent) drove the value. The key is to recognize whether your startup’s value proposition lies in a unique technology – if so, patents become crucial to maximize that value during exit, whereas if your advantage is more market-based, patents might play a more minor role. Even then, holding a few patents can act as an “insurance policy” or bargaining chip. For example, a startup without patents could be vulnerable to patent infringement suits post-acquisition (making it less attractive to buyers concerned about IP risks). In contrast, a startup with even a small patent portfolio might deter opportunistic litigation and provide a starting point for defensive IP strategies by the acquirer.

Industry and Geographic Variations in Patent Strategy

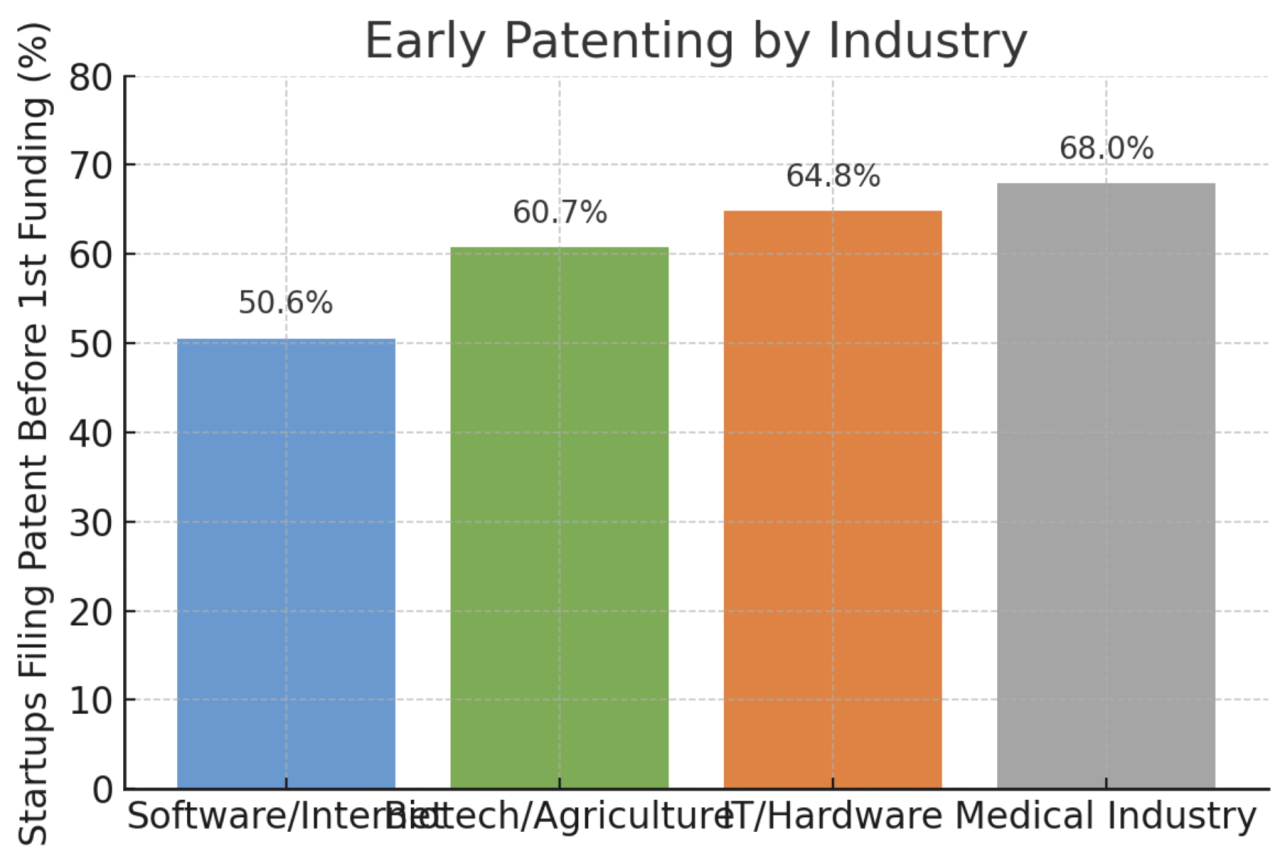

The importance and usage of patents vary dramatically by industry. Founders should calibrate their IP strategy to the norms of their specific sector. Broadly, startups in life sciences and deep-tech fields patent at much higher rates than those in software or internet services. Lerman’s cross-industry study found that, on average, about 23% of tech startups file for patents, but this average masks a big split: in Biotechnology, Medical Devices, and Hardware, startups tend to patent significantly more than in the Software/Internet domain.

In fact, only around one in five Software/Internet startups had any patents in the dataset (about 19%), whereas patenting was far more common in biotech and hardware sectors.

This makes intuitive sense. In biotech or pharma, a patent on a new drug or bioengineering technique is often mandatory for attracting investment – without IP protection, a new drug compound is practically un-fundable. Similarly, hardware and semiconductor startups frequently rely on patented engineering advances that require years of R&D, so they accumulate patents as a natural byproduct of innovation. In contrast, software startups can sometimes rely on speed to market or trade secrets; given the fast iteration cycles and the abstract nature of software, patents (especially after the 2014 Alice decision limiting software patentability) are seen as less vital.

Figure: Percentage of tech startups that file their first patent before raising any funding, by industry (based on U.S. data 2008–2012). Patent-intensive sectors like biotech, hardware, and medical devices tend to seek IP protection very early, with over 60% filing patents pre-funding. In contrast, only about half of software/internet startups that patent do so that early (Lerman, 2018). This reflects differences in product cycles and the perceived necessity of patents for proving the business case in each sector.

The figure above underscores how industry differences affect patent strategy. Not only do biotech and hardware startups patent at higher rates, they also do so earlier in their lifecycle (more on timing in the next section). Founders should be aware of the norms in their space: if you’re in an industry where every credible startup has at least a couple of patents (e.g. medical devices), not having any can be a glaring red flag to investors and partners. Conversely, in an industry like consumer internet, having a patent might be a nice-to-have but will not make or break your fundraising if you have strong traction and growth metrics. In those sectors, investors might value speed and user growth over patents, and indeed pursuing a patent too aggressively could even signal misaligned priorities (e.g. a social app startup diverting lots of effort to patents instead of user acquisition might worry investors). Thus, know your industry’s patent benchmark. If unsure, observe your direct competitors or ask mentors/investors in your domain about the expected IP posture at various stages.

Geography also plays a role. Even within tech hubs in the United States, patenting behavior differs. Startups in California (especially Silicon Valley) are more likely to patent than those in many other states (Lerman, 2018). This holds true even after controlling for company size and funding, suggesting a regional culture that places a higher emphasis on IP. Several reasons have been suggested: Silicon Valley’s competitive environment and fast-scaling mindset might encourage securing patents as strategic assets; also, California’s ban on non-compete agreements means companies cannot prevent employee poaching, so they may use patents to secure exclusivity around their technology instead. Other states show patterns tied to industry mix. For example, Massachusetts (with its concentration of biotech) has a high rate of startup patenting, while New York (dominated by finance, media, and software startups) sees lower patent counts on average. Internationally, differences can be even more pronounced due to varying legal systems and market focuses. In Israel – often dubbed the “Startup Nation” – tech startups pursue patents to signal global competitiveness, particularly because many aim to sell into U.S. or European markets where IP is valued. European startups, operating under a stricter first-to-file and costly European Patent system, may be more selective with patent filings, focusing on key inventions and markets.

The takeaway is that context matters. Founders should factor in both industry and regional norms when crafting an IP strategy. If you’re launching a medical device startup in Boston, robust patent filings will almost be a prerequisite for serious funding. If you’re building a fintech software company in New York, investors might care more about regulatory approvals or user acquisition than patents – but if you do have a truly novel technical method, a patent could still give you an edge (and signal that you’re a technology leader among peers). Always align your patent efforts with the expectations of your investor and customer community.

When to File: The Timing of Patent Applications

For startups that decide to pursue patents, a critical question is when to start the process. Filing too early can drain resources and potentially disclose ideas before the product is fully baked; filing too late can mean losing the race to competitors or missing a window to signal value to investors. Empirical data shows that many startups file their first patent extremely early – often before any outside funding is secured. In Lerman’s dataset, of all the startups that eventually patented, 56% filed their first patent before raising a seed/Series A round. About 28% filed shortly after the first round, and only a minority waited until second or later funding rounds. Virtually none waited beyond a third round to patent – by that stage, if a company hadn’t filed a patent, it likely never would.

Why do so many founders patent early, despite the costs? One reason is the signaling effect discussed earlier – a patent application in process can be a positive talking point in fundraising meetings. In patent-intensive industries, early filing is also necessary to lock in rights on core technology before engaging openly with investors, partners, or customers. Another reason is the legal environment: since the U.S. (and most of the world) shifted to a first-to-file system (effective 2013 in the U.S.), being the first to submit a patent application can make the difference between owning the invention or not. Startups face pressure to file as soon as they have a clear innovative concept, because any delays introduce risk that someone else (a competitor or even a former employee) could file a similar idea first, or that the startup’s own public disclosures could jeopardize patentability. The data by industry reflects this – in biotech or hardware, where R&D cycles are long, companies know they have patentable IP early on and tend to file preemptively (over 60% do so before any funding). In software, some startups may delay patenting until they have an initial product or traction (nearly half of software startups that patent wait until after securing funding) . This can be due to the faster iteration cycle (founders might pivot the product before bothering to patent) and the fact that software patents can be tricky in terms of eligibility and scope.

From a strategic standpoint, earlier is better for critical patents, but with some caveats. Filing a provisional patent application is a popular strategy for early-stage startups: a provisional is a relatively low-cost, low-disclosure way to secure a filing date and say “Patent Pending” while buying up to 12 months to file a full application. This was echoed by Lerman, who noted that provisional filings can “provide access to the potential value of patent signaling without the costs of a full patent application." In practice, a startup might file a provisional as soon as they have a working prototype or detailed concept, then use the next year (hopefully after raising a seed round) to fund the preparation of a robust non-provisional application. This approach balances cost and speed.

Founders should also time their patent filings to fundraising and product milestones. If you know you’ll be pitching VCs in six months, having at least a provisional filed (so you can mention a “patent pending”) can strengthen your story. On the other hand, rushing a patent out the door just to impress investors, before you’ve nailed down the core invention, can backfire – you might end up with a narrow patent that doesn’t actually cover your final product or that misses key claims. Therefore, treat patent timing as a strategic project: identify your startup’s key innovations and plan to patent them at a time that maximizes both legal advantage (securing the earliest priority date) and business advantage (coinciding with fundraising or partnership discussions). Keep in mind the patent office’s timelines too. Even after filing, it often takes 2–4 years to get a patent granted, which for a fast-growing startup is a long time. There are procedures to accelerate examination (e.g. the USPTO’s Prioritized Examination or similar programs abroad), which might be worth using for at least one flagship patent if having an issued patent soon is important for attracting investment or deterring copycats. Given that studies have shown young startups benefit significantly once a patent is granted (Greenberg, 2013), a case can be made to fast-track the process where feasible.

Patent Applications vs. Granted Patents: Does It Make a Difference?

Startups often wonder whether a patent pending status is enough, or if they need an actual patent in hand to reap benefits. The reality is that even pending patent applications confer some advantages, but a granted patent can elevate those benefits, especially at certain stages. Investors generally view patent pending as a positive signal – it shows the founders are serious about protecting IP and presumably have something novel. As noted earlier, Lerman’s analysis found that the positive effects on funding and acquisition were already apparent just from patent applications (the data she used was based on filings, regardless of whether they had issued yet). This suggests that simply having filed for IP protection can boost a startup’s credibility in early phases. From an investor’s perspective, a pending application is often sufficient at the seed stage to check the “IP box.” After all, the seed investor might assume (or hope) that by the time an exit comes, the patents will have issued. In the meantime, the fact that an application is on file and will eventually publish also serves to stake out a claim that can deter some competitors from pursuing the exact same idea.

However, a granted patent provides a different level of assurance. Once a patent is granted, the scope of the legal protection is clearer (claims have been examined and allowed), and the startup officially has an enforceable right. The Israeli study by Greenberg makes this distinction clear: while patent applications were associated with higher valuations across the board, the additional impact of a patent grant was “positive and significant for younger firms in early financing rounds, but small and insignificant for more mature start-ups."

In practical terms, for an early-stage startup raising a Series A, getting that patent granted could bump the valuation or make investors more confident – it reduces uncertainty about whether the company truly has defensible IP. For a later-stage startup with revenue and customers, whether a patent is still pending or issued might not matter as much, because by then the business has other demonstrated value (and perhaps multiple filings in the pipeline). Venture capitalists have noted that by growth stage, patents become one of many assets and not a primary driver of valuation.

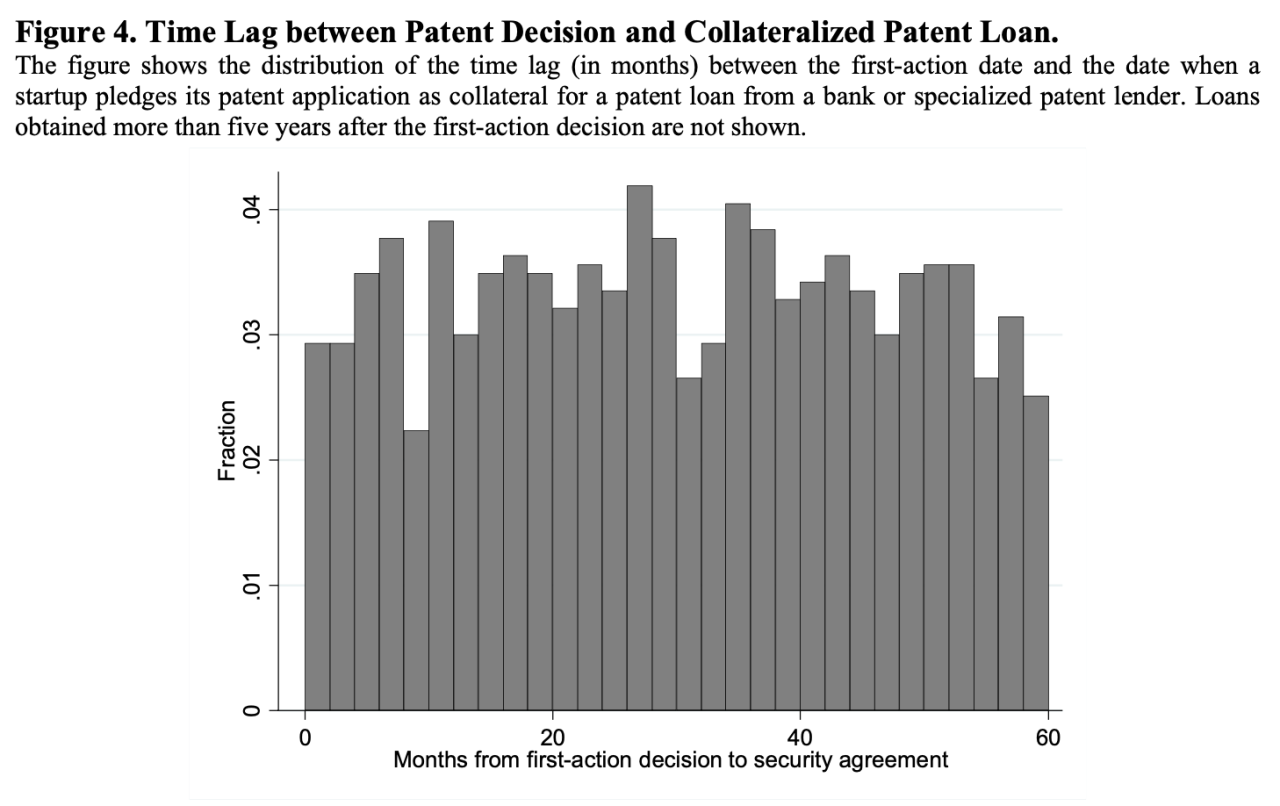

Another area where an issued patent can make a big difference is in securing debt or strategic partnerships. Banks and lenders typically won’t consider a pending patent as collateral, but once it’s issued, a patent can be used to secure loans (as evidenced by the 76% increase in loan likelihood in the patent lottery study). Large corporate partners may also place more stock in a granted patent if they are considering licensing the technology or investing in the startup – it de-risks the deal for them. Additionally, only granted patents can be enforced in court; if a competitor is infringing your technology, having the issued patent is necessary to actually stop them or seek damages. During the pending period, you have no enforceable rights (aside from some provisional damages in certain jurisdictions).

For founders, the implication is: don’t ignore your patent applications after filing. It can be tempting to file a provisional or non-provisional and then put IP on the back burner while you focus on the business. But you should monitor and manage the process to get important patents issued in a reasonable timeframe. If you’re an early-stage company and one particular patent could significantly enhance your credibility or freedom to operate, consider pursuing accelerated examination for that application. And if you’re deciding between filing a broader patent that might take longer to negotiate/examine versus a narrower one that could get allowed sooner, weigh the trade-offs in light of your fundraising schedule. Sometimes getting a first patent issued (even if narrow) can be more valuable in the short term than having a perfect, broad patent stuck in years of examination. You can always file continuations to broaden scope later. In sum, a patent pending is good, but a patent granted is better – especially when you’re still young and trying to prove yourself.

Policy Factors: Patent Delays and First-to-File Systems

Founders should also be aware of the broader patent policy landscape, as it can impact startup strategy. Two key policy-related factors are the patent grant lag (time to issuance) and the first-to-file priority rule. We’ve touched on both in passing, but let’s unpack their significance.

Patent grant lag: Startups operate on rapid timelines, but patent offices do not. In the U.S., the average time from filing to grant is often 2–3 years (and can be longer in high-tech fields or if there are rejections to overcome). In Europe, it’s similar or longer. This lag means a startup could go through several funding rounds, or even go public or get acquired, before its patents issue. The lag creates uncertainty – as discussed, investors and partners might discount the value of a pending patent compared to a granted one. Recognizing this, some patent offices have introduced programs to expedite examination for startups or important technologies. For example, the USPTO’s Track One program (for a fee) can get a patent final decision within 12 months. There are also pilot programs that fast-track patents for small businesses or for inventions in certain areas (like green technologies). However, not all startups know about or utilize these programs due to cost or oversight.

From a policy perspective, researchers like Gili Greenberg suggest that a “more speedy examination process of younger firms’ patent applications” could enhance startups’ ability to attract financing. The logic is straightforward: if a patent could be granted in, say, one year instead of three, a startup would more quickly reap the signaling and protective benefits during the critical early window of growth. Policymakers concerned with innovation might consider subsidies or automatic fast-tracking for verified startups (for instance, those under a certain revenue/employee threshold) to reduce the grant lag. Until such ideas are implemented widely, founders need to be proactive themselves: if having a patent granted sooner will materially help your business, factor the acceleration fee or attorney efforts into your plans. The cost of fast-tracking might be small compared to the boost in a venture round or valuation that an issued patent could confer in the right circumstances.

First-to-file vs. first-to-invent: The global norm now is first-to-file – meaning the patent goes to whoever files the application first (assuming it’s deemed novel and non-obvious), not necessarily the first person who conceived the idea. The U.S. transitioned to first-to-file in 2013 to harmonize with other countries. For startups, this rule emphasizes speed and secrecy. You no longer have the safety net of proving you invented something first if someone else beats you to the patent office. This intensifies the “race” to file patents. It also means that any public disclosure before you file can be extremely dangerous. In the U.S., there is still a one-year grace period for an inventor’s own disclosure – if you publish or demo your invention, you have up to a year to file a U.S. patent. But most other countries have zero grace period. So a startup that pitches its product at a conference or posts on GitHub before filing could immediately lose patent rights in Europe, China, and elsewhere. Founders must therefore manage their IP and publicity strategy carefully. The best practice is usually: file at least a provisional patent before any public reveal of the technology. If you need to talk to beta users or potential partners pre-filing, use nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) to maintain it as a confidential disclosure (which doesn’t count as a public disclosure). The first-to-file regime essentially forces startups to think about IP earlier in the development process than they might otherwise. It can be inconvenient and feel premature, but that is the trade-off for preserving the opportunity to patent at all.

There’s also a fairness aspect here that is sometimes raised: first-to-file can favor those with more resources (who can file quickly and often). A big corporation can file patents at the drop of a hat, whereas a cash-strapped startup might delay. This is another reason why some advocate for policies to support startup patenting, such as reduced fees (the U.S. does offer 50-75% fee reductions for small and micro entities) and patent clinics that help startups. Still, the system is what it is, and startups need to play by those rules to compete. Being first-to-market is great; being first-to-file can be just as important for long-term IP position.

Finally, another subtle policy issue is the breadth and enforceability of patents – which can change with legal precedents. For instance, changes in what is considered patentable subject matter (like the aforementioned Alice ruling on software or the Mayo and Myriad decisions on biotech) can alter how valuable a startup patent ends up being. While founders can’t control court decisions, they should stay informed via their IP counsel about shifts in patent law that might affect their portfolio. Sometimes pursuing an alternative IP strategy (trade secrets, copyrights, etc.) is wiser if the legal landscape is unfavorable for patents in your domain.

The policy environment puts the onus on startups to file early and strategically. Patents take time, so plan ahead, and leverage any available mechanisms to speed things up if needed. The early bird gets the worm – or in this case, the patent.

Strategic Takeaways for Startup Founders

Integrating these insights, what actionable advice can we offer to startup founders about patents? Here are some key takeaways and best practices for treating IP as a strategic asset:

Align Patent Strategy with Your Business Strategy: Use patents to support your startup’s core value proposition. If your competitive advantage hinges on a technical innovation, securing a patent on that innovation should be a priority. If your advantage is more about market execution (e.g. network effects or brand), patents may be a lower priority but can still add ancillary value (for example, a patent on a behind-the-scenes process). Make sure any patent efforts map to something that truly matters for your business’s success or valuation.

File Early, But Use Provisional Applications to Your Advantage: Given first-to-file rules, it’s wise to file as early as feasible on key inventions – often earlier than you might think. Take advantage of provisional applications to lock in a priority date with minimal cost and formality. This gives you a year to test the waters and gather resources for a full application. For example, a garage-stage startup could file a provisional for a few hundred dollars covering the core concept, then use that year to refine the product and raise seed funding, and convert to a full (non-provisional) application once funded. Caveat: Don’t file so hastily that your application is junk – you need enough detail in a provisional to be worth the paper it’s on. Work with a patent attorney to draft a solid provisional when possible.

Patents as Fundraising Leverage: If you are approaching investors, having at least a patent pending (or better, an issued patent) can strengthen your pitch. Emphasize how your IP secures your technology and can even be used offensively or defensively if needed. Be ready to explain your patent strategy: Why is it novel? What’s the scope? How does it deter competitors? This can impress sophisticated investors. At the same time, be prepared for savvy VCs to probe the business relevance – they know a long list of patents isn’t useful unless it protects something that drives profits. So, be strategic: one well-placed patent on your “secret sauce” is more persuasive than ten peripheral patents.

Balance Quantity and Quality: Data shows that number of patents correlates with funding, but you should avoid a vanity patent count. Each patent costs tens of thousands of dollars (including attorney and filing fees) and significant management time. For a cash-limited startup, there is an opportunity cost to filing numerous patents. Focus on quality: pursue broad, hard-to-design-around patents if you can, rather than many narrow ones. If you have multiple inventions, prioritize those that are most central to your product and most likely to be valuable (either to enforce, license, or signal innovation). Remember the study where only “useful” patents drove valuation – make sure your patents would be considered useful in the eyes of an acquirer or investor. That said, if you have a genuine treasure trove of innovations (common in deep tech), don’t be shy about patenting aggressively to build an IP fortress, especially if investors are providing capital for it.

Leverage Patents in Partnerships and Defense: Beyond investors, patents can influence other stakeholders. If you seek strategic partnerships or enterprise customer deals, having patents can make your small startup a safer bet (the partner knows you have some IP ownership of the tech). Patents can also deter larger rivals from litigating or copying – they know you have at least a bullet in the chamber if things go to court. However, be realistic: a patent portfolio is not an impenetrable shield, and enforcing patents is expensive. Think of patents more as bargaining chips that give you options (licensing opportunities, defensive countersuits, etc.) rather than as guaranteed protection.

Don’t Let IP Distract from Product-Market Fit: It’s easy to get so caught up in patents that you lose sight of building, selling, and iterating on your product. Patents should support your business, not consume it. Allocate a sensible portion of your budget and time to IP – for instance, plan an IP strategy review every few months, not every day. Use experienced counsel or advisors to lighten the load; many law firms have startup-friendly arrangements (deferred fees, flat packages for provisionals, etc.). Once you file, you can often “pause” heavy IP work for a while before the next stages come due, which allows you to focus on core business in the interim. In short, get your IP in order, then get back to building your company.

Know When Not to Patent: Not every innovation should be patented. Some things are better kept as trade secrets – e.g. algorithms, formulas, or business methods that are hard to reverse-engineer and where disclosure would give away too much. Patents are public disclosures; after 18 months, your application will be published for all to see. If your secret sauce can remain secret and gives you an edge, you might skip patenting it (common examples: Google’s search algorithm was never patented; Coca-Cola’s recipe is a trade secret). Also, if the cost is prohibitive and the likely benefit small (say your invention is in a niche market or will be obsolete in a year), a patent might not be worth it. Each startup’s situation is unique – it’s perfectly valid to have zero patents if that’s the rational strategy for your business model. Just be deliberate in that choice rather than ignoring IP by default.

Patents can be powerful tools for startups – facilitating funding, adding credibility, and paving the way to successful exits – but they are tools that must be used wisely. The research evidence shows a clear positive correlation between patents and startup success indicators like VC investment and acquisitions, and even provides causal evidence that patents can accelerate growth. Founders should neither undervalue nor overvalue patents: view them as one component of your venture’s strategy. By understanding the dynamics of your industry, filing smart and early, and balancing IP efforts with business needs, you can harness patents to strengthen your startup’s trajectory. And if you choose to forego patents, do so with full awareness of what you’re trading off. In the high-stakes game of startups, intellectual property is often an ace up your sleeve – play it at the right time, and it just might significantly boost your odds of winning.