In the modern, high-stakes theater of corporate R&D, a phenomenon has taken root that is both statistically observable and logically baffling. Academics—who seem to derive a specific, dry pleasure from naming things that don’t make sense—call it the "Patent Paradox."

Here is the gist: Over the last few decades, the rate at which companies obtain patents per dollar spent on research (a metric technically known as "patent intensity") has gone vertical. Skyrocketed. Yet, simultaneously, the expected value of any single, individual patent has appeared to decline.

This presents a fascinating contradiction to the classical theory of why patents exist at all. The traditional justification—the one mumbled by fatigued 1L law students for generations—is that a patent acts as a temporary monopoly. It is a legal shield erected around a discrete innovation to prevent "free-riders" from stealing the fruits of your intellectual labor.

But if the value of the shield is diminishing, why are rational, profit-maximizing companies acquiring them at a velocity that suggests panic?

The answer has profound implications for corporate strategy, competition, and the very nature of innovation. The fundamental unit of analysis has shifted. We are no longer looking at the patent; we are looking at the portfolio.

The Unit vs. The System: A New Theory of Value

This shift is the core of what Gideon Parchomovsky and R. Polk Wagner termed the "Patent Portfolio Theory." Their insight—which feels obvious only in retrospect—is that w/r/t patents, the whole is demonstrably greater than the sum of its parts.

A portfolio creates value through synergy. It transforms Intellectual Property (IP) from a static legal function (a thing lawyers do in the basement) into a dynamic strategic function (a thing the C-suite worries about in the penthouse).

The Two Engines of Portfolio Value

To understand strategic patent management, you have to understand the two mechanisms that drive it:

Scale (The Thicket): A single patent is fragile. It can be "designed around" by a competitor with a decent engineering team and a lack of scruples. But a "patent thicket"—a dense web of hundreds of overlapping patents covering every conceivable incremental variation of a technology—is a fortress. It creates a deterrent effect. It makes the cost of navigating your IP prohibitively expensive for rivals.[^1]

Diversity (The Moat): This refers to breadth. A diverse portfolio protects not just the widget, but the ecosystem around the widget. It covers upstream components, downstream applications, and adjacent technologies. It is a form of insurance. If one patent falls in court, the phalanx remains.

Navigating the Tensions of Modern IP Strategy

Sounds too easy: build a portfolio with scale and diversity. But the realities of implementing such a framework is far from easy or simple.

The shift to a portfolio-centric view was not merely a change in tactics; it was driven by a fundamental expansion of strategic intent. The traditional motive for patenting—to protect an invention from imitation—is still relevant, but it has been joined by a host of other, more aggressive and nuanced strategic motives. This creates the first and most critical tension in portfolio management: the push and pull between building a portfolio for pure protection versus building one for strategic leverage.

A seminal 2007 study by Blind, Cremers, and Mueller provided clear empirical evidence of this dynamic. They analyzed the patenting motives of over 400 German companies and correlated those motives with the measurable characteristics of their patent portfolios.8 Their work gives us a powerful framework for understanding the different "jobs" a patent portfolio can be hired to do.

Indeed, the transition from "we have a patent" to "we have a strategy" is not a simple linear progression. It is a landscape defined by a series of powerful, often conflicting tensions that pull the modern IP manager in several directions at once.

1. The Tension of Intent (Protecting Crown Jewels vs Creating Leverage)

The traditional motive, which the study labels the protection objective, is focused on securing a core innovation from being copied. When this is a firm's primary goal, it invests heavily in obtaining a few, high-quality patents with broad, defensible claims. The study found a clear and significant correlation: the more a company's patenting is driven by the protection motive, the higher the average number of citations its patents receive.8

The study found a clear and significant correlation: the more a company's patenting is driven by the protection motive, the higher the average number of citations its patents receive.

Under this model, patent citations are a critical, if imperfect, proxy for a patent's value and technological significance.9 Pioneering research by scholars like Manuel Trajtenberg demonstrated that while raw patent counts are poor indicators of value, citation-weighted counts show a strong correlation with the social and economic welfare created by an innovation.9 A patent that is frequently cited by later inventions is likely a foundational piece of technology—one that stands on the "shoulders of giants," to borrow Suzanne Scotchmer's famous phrase.11 Therefore, a portfolio built for protection is, by its nature, a collection of "crown jewel" patents. Each one is intended to be a strong, valuable asset in its own right.

But then there is Strategic Leverage. This is where things get Machiavellian.

In contrast to the protection motive, the study identified several strategic motives that have become increasingly prevalent. These are not about protecting a single invention, but about shaping the competitive landscape.

Offensive Blocking: Patenting adjacent technologies just to block a competitor’s R&D path. It’s like buying all the land around your neighbor’s house so they can’t build a driveway.

Defensive Blocking: This is a more reactive strategy, aimed at preserving a company's own freedom to operate. By patenting incremental improvements and variations around its own technology, a firm can prevent competitors from patenting those same variations and then using them to sue the original innovator. The study found this motive to be closely related to the traditional protection motive, suggesting it is a forward-looking form of defense.

Bargaining Chips: In complex sectors like semiconductors, everyone is infringing on everyone else all the time. It is impossible not to. In this scenario, a massive portfolio isn’t a shield; it’s currency. It allows for cross-licensing agreements. It says, "I won't sue you for infringing my 500 patents if you don't sue me for infringing your 500 patents."[^2]

This research illuminates the central tension of intent. A company cannot simultaneously optimize for all motives. A strategy focused on creating a few, high-value "crown jewel" patents for pure protection is fundamentally different from a strategy focused on creating a high-volume "patent thicket" for offensive blocking or exchange. The former prioritizes individual patent quality (as measured by citations), while the latter prioritizes portfolio quantity and density.

This tension forces a critical strategic choice. Is the goal to have the single strongest patent in a legal battle, or to have a wall of 100 patents that makes a legal battle too costly for a competitor to even consider? The answer depends entirely on the company's business model, its competitive environment, and its long-term strategic objectives. The failure to consciously make this choice is one of the most common pitfalls in portfolio management, leading to a collection of patents that is neither a strong shield nor an effective strategic weapon—it is simply an expensive hobby.

2. The Managerial Tension (Cost Center vs. Value Driver)

Historically, the patent department was a Cost Center. It was a hole in the floor into which the CFO threw money to pay for filing fees and lawyers. Today, a well-managed portfolio is a Strategic Business Asset.

This creates friction. The legal team is trained to mitigate risk (Defense). The business team wants to grow revenue (Offense).

Indeed, the expansion of patenting from a purely protective legal function to a complex strategic one has created a significant tension within the modern corporation. Historically, the intellectual property department was a legal cost center. Its job was to file patents and manage risk, and its budget was an expense to be minimized. Today, however, a well-managed patent portfolio is recognized as a primary driver of corporate value, capable of attracting investors, influencing M&A valuations, generating licensing revenue, and serving as collateral for financing.

This creates a fundamental push-and-pull dynamic between the legal and business functions of a company. The legal team, trained in risk mitigation, often defaults to a defensive posture. The business team, focused on growth and ROI, needs the IP portfolio to be an offensive tool. This disconnect is often a source of immense friction and missed opportunity. As William Fisher III noted in the California Management Review, engineers, lawyers, and business executives often lack a common framework and language to develop an integrated approach to IP and firm strategy. Lawyers are often brought in too late, after a product is already developed, and are forced to say "no" rather than being able to shape the product's design to reflect legal opportunities from the start.

Resolving this tension requires elevating patent management from a siloed legal task to a core, cross-functional strategic process. Success is rooted in a triad of a clear strategy, a supportive organization, and sophisticated core processes. A brilliant strategy is useless if the organization is not structured to implement it.

This means creating a culture and a set of processes where the patent strategy is not an afterthought, but is derived directly from the corporate vision and mission. It requires a continuous dialogue between the C-suite, R&D, and legal counsel to ensure that every decision—from which inventions to patent, to which jurisdictions to file in, to which patents to maintain or abandon—is aligned with the company's overarching business goals.

The companies that manage this tension effectively are the ones that treat their patent portfolio not as a collection of legal documents, but as a dynamic business tool. They understand that the true value of the portfolio comes from how it is managed and integrated into broader business strategies. This requires a new set of frameworks for thinking about and managing intellectual property.

Resolving this requires elevating patent management from a siloed task to a cross-functional discipline.

3. The Tension of Time (Legacy vs. Blue-Sky)

Companies are often haunted by their own past. A massive chunk of the budget is often spent protecting the innovations of yesterday (maintenance fees), leaving little for the "blue-sky" IP that defines the future.

This is where Frameworks become necessary to stop the madness.

Frameworks for Sanity: Managing the Portfolio

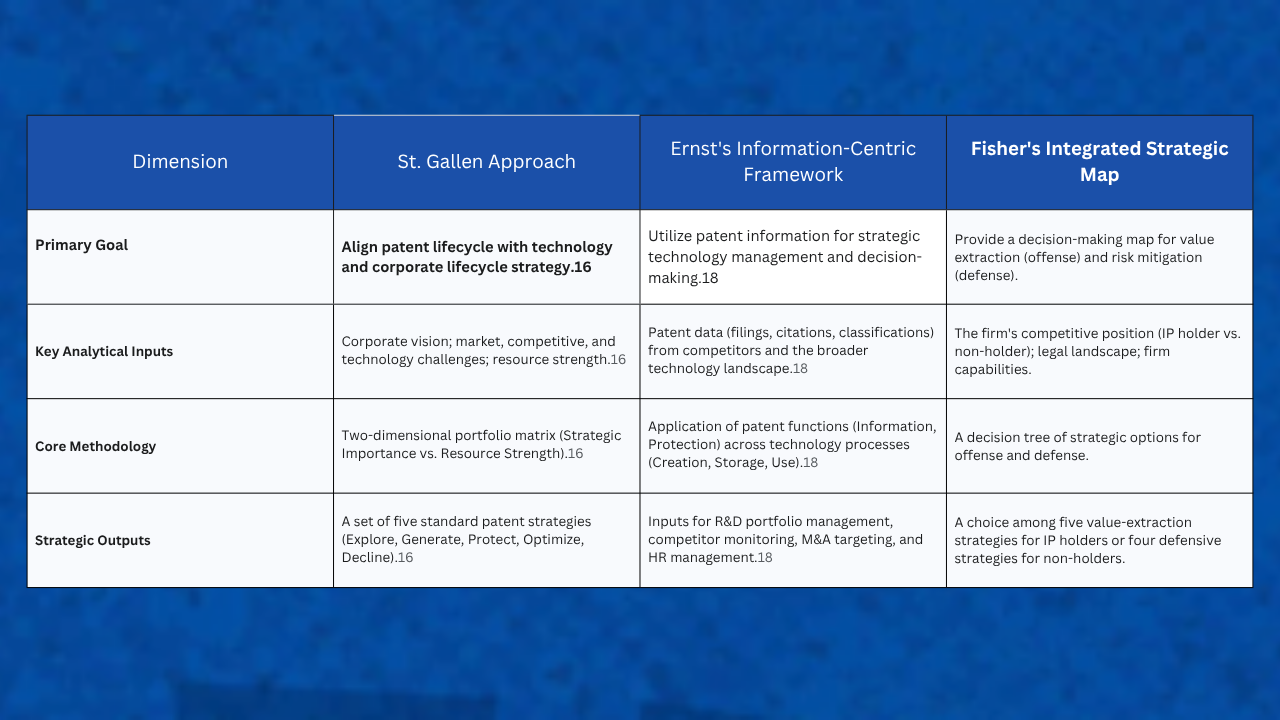

You cannot manage this complexity by gut feel. The literature provides several models to bridge the gap between legal minutiae and business strategy. These are not rigid, prescriptive models, but rather strategic lenses that can help clarify the trade-offs and guide decision-making. Three of the most influential are the St. Gallen approach, Ernst's information-centric framework, and Fisher's integrated strategic map.

The St. Gallen Approach (The Lifecycle Lens)

Developed at the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland, this framework provides a rigorous, top-down methodology for aligning the patent lifecycle with the technology and corporate lifecycle. The process begins with the company's vision and mission and assesses the technological challenges from the perspective of customers, competitors, and potential substitute technologies.

The core of the framework is a two-dimensional "Technology Portfolio" matrix. It maps the company's technological competencies based on their Strategic Importance and the Relative Strength of the company's resources in that area. This analysis yields five standard technology strategies, which directly correspond to a typical product lifecycle:

Observe: For emerging technologies of low current importance.

Study: For technologies of growing importance where the company is building initial competence.

Invest: For core technologies with high strategic importance and strong internal resources.

Optimize: For mature technologies where the focus is on ROI, not further investment.

Divest: For declining technologies with no foreseeable competitive advantage.

From this technology portfolio, a corresponding "Patent Portfolio" with five parallel strategies is derived: Explore, Generate, Protect, Optimize, and Decline. Each phase dictates specific patenting actions. In the "Explore" phase, the company might conduct broad patent searches and file patents with wide claims on promising new concepts. In the "Protect" phase for core technologies, the focus shifts to filing patents with broad claims, monitoring major competitors, and defining a global protection strategy. In the "Decline" phase, patents are reviewed for abandonment or sale to cut costs.

The power of the St. Gallen approach is its explicit linking of patent activity to the strategic lifecycle of the business. It provides a clear answer to the tension of time: it forces managers to think about which technologies are in the past (Decline), which are the present (Protect/Optimize), and which are the future (Explore/Generate), and to allocate patent resources accordingly.

Ernst's Information-Centric Framework: The Data Lens

Holger Ernst's framework, developed in 2003, reframes the patent system itself. It argues that patents serve two primary functions: Information and Protection. These functions are then applied across the three core processes of technology management: Creation, Storage, and Use.

This framework highlights the often-underutilized value of patents as a source of competitive intelligence. For example:

In Technology Creation, the information function of patents is used to monitor competitors' R&D strategies, assess the technological landscape, and identify potential M&A targets or alliance partners.18 Analyzing patent filing trends can provide crucial insights into a competitor's future plans long before a product is launched.

In Technology Use, the protection function is used not only to protect products from imitation but also to gain strategic advantages through cross-licensing or patent sales.

Ernst's framework is particularly relevant in the modern era of big data. It positions patent analytics not as a niche legal task, but as a central competitive intelligence function that should inform R&D portfolio management, M&A strategy, and even human resource management (by identifying key inventors at competing firms).It provides a powerful argument for transforming the patent department from a cost center into an intelligence hub.

Fisher's Integrated Strategic Map: The Game Theory Lens

William Fisher's framework, published in the California Management Review, provides a practical decision-making "map" for both offensive and defensive IP strategy. It is explicitly designed to facilitate the crucial conversation between managers, lawyers, and innovators.

For IP Holders (Offense), the framework challenges the default assumption that the best strategy is always to suppress competition. It outlines five distinct ways to extract value from an IP right:

Exercising Market Power: The traditional exclusion model.

Selling the IP Right: Assigning the patent to another firm where it might be more valuable.

Licensing the Right: Granting permission to others, including competitors, to use the IP in exchange for royalties.

Organizing Collaborations: Using the IP as a basis for joint ventures or other partnerships.

Giving the Right Away: Waiving the right, for example, to help establish a technology as an industry standard.

For Firms Lacking IP (Defense), the map presents alternatives to costly litigation:

Developing a Non-Infringing Alternative: Inventing around the competitor's patent.

Securing a License: Paying for the right to use the technology.

Building a Defensive Portfolio: Accumulating patents to deter litigation through the threat of a countersuit (mutually assured destruction).

Deploying Rapidly: Launching a potentially infringing product so quickly and widely that it creates a new market reality, making it difficult for a court or the IP holder to unwind.

Fisher's framework excels at highlighting the strategic trade-offs. It forces a company to move beyond a simplistic "sue or be sued" mentality and consider a much richer set of strategic options. It directly addresses the tension between value capture (taking a larger slice of the pie) and value creation (making the pie bigger for everyone), noting that an aggressive focus on the former can often be detrimental.

These frameworks, while different, all point to the same conclusion: strategic patent management is an active, not a passive, discipline. It requires a system.

The Operational Reality: Audit, Optimize, Prune

A patent portfolio is not a collection of trophies to be dusted occasionally. It is a garden that requires weeding. This brings us to the most painful part of the process: Strategic Abandonment.

Patents are expensive. Maintenance fees (annuities) accumulate. A large portfolio can bleed millions of dollars annually. The cornerstone of optimization is the Portfolio Audit. You must ask the uncomfortable questions:

Is this patent protecting a product we actually sell?

Is the technology obsolete?

Are we paying to protect a "ghost" asset?

Pruning—allowing patents to lapse—is culturally difficult. Inventors hate it. It feels like admitting failure. But financially, it is imperative. Every dollar saved on a zombie patent is a dollar invested in a new AI filing.

The Future: AI and the Death of Intuition?

Finally, we arrive at the tension that will define the next decade: Human Intuition vs. AI Augmentation.

For a long time, patent strategy was an art form practiced by wizened attorneys. Now, it is becoming a data science. Artificial Intelligence is reshaping the landscape:

Operational Efficiency: AI automates the banal work of prior art searches.

Valuation: Algorithms can now predict the commercial value of a patent by analyzing citation networks and market data better than humans can.

Predictive Strategy: AI can identify "white space" in the technological landscape—areas where no one has patented yet—allowing firms to file preemptively.

The strategist of the future will not be a lawyer with a highlighter; they will be a cyborg-like synthesis of legal expertise and algorithmic predictive power.[^3]

Notes

[^1]: This theory relies on the "Rational Actor" model of economics, which assumes everyone is acting logically and with perfect information. Anyone who has ever attended a product roadmap meeting knows this is, at best, a charming fiction.

[^2]: This is often referred to as "Mutually Assured Destruction" (MAD) in the IP world. It is the corporate equivalent of stockpiling nuclear warheads to ensure peace. It is expensive, terrifying, and regrettably effective.

[^3]: This assumes, of course, that the AI is not hallucinating, and that "white space" isn't empty simply because it's a terrible idea that no one wants.

The Conversation Continues

If you are currently staring at a spreadsheet of 4,000 patents, feeling the specific weight of the "sunk cost" fallacy, and wondering which assets are actually alive, we should probably speak: https://outlierpatentattorneys.com/contact

Works cited

Patent Portfolios - Penn Carey Law: Legal Scholarship Repository, accessed October 7, 2025,

Using Patent Portfolio to Effectively Manage Technical Assets: The Mechanism of Patent Portfolio to Influence Firm Performance - SciTePress, accessed October 7, 2025,

(PDF) Patents as Indicators for Strategic Management - ResearchGate, accessed October 7, 2025

Patent Portfolio Management: Strategy, Value & Best Practices - The National Law Review, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent Portfolio Management: A Penny Saved is a Penny Earned | Miller Nash LLP, accessed October 7, 2025,

A Study on Patent Strategy and Management, accessed October 7, 2025,

The Impact of Patent Portfolio Diversity on Firm Performance in Digital Enterprises—The Moderating Role of Regional Digital Economy Development Levels - ResearchGate, accessed October 7, 2025,

The Influence of Strategic Patenting on Companies' Patent ... - ZEW, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent research in academic literature. Landscape and trends with a focus on patent analytics - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent research in academic literature. Landscape and trends with a focus on patent analytics - Frontiers, accessed October 7, 2025,

How do patents affect research investments? - PMC, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent management: the prominent role of strategy and organization - Emerald Publishing, accessed October 7, 2025,

Maximizing IP Value: A Guide to Strategic Patent Portfolio Management - Patentskart, accessed October 7, 2025,

IP Rationalization: Making Portfolio Decisions Aligned with Growth | PatentPC, accessed October 7, 2025,

Intellectual Property as a Strategy for Business Development - MDPI, accessed October 7, 2025

(PDF) Strategic Management Of Patent Portfolios - ResearchGate, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent portfolio management: literature review and a proposed model, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent information for strategic technology ... - LexisNexis IP, accessed October 7, 2025,

Patent Landscape Analysis: Actionable Insights for Strategic Decision Making - UnitedLex, accessed October 7, 2025,

Strategic Management of Intellectual Property - Harvard Business ..., accessed October 7, 2025,

5 tips for managing your patent portfolio - IP Insights - Wilson Gunn, accessed October 7, 2025

Optimize Patent Portfolio with Strategic Abandonment - TT Consultants, accessed October 7, 2025,

Portfolio Optimization: Best-Practices Strategies to Maximize Value - UnitedLex, accessed October 7, 2025,

Value capture in open innovation markets: the role of patent rights for innovation appropriation - Emerald Publishing, accessed October 7, 2025,

Strategic Management of Open Innovation: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective, accessed October 7, 2025,

(PDF) Intellectual Property Management in Open Innovation - ResearchGate, accessed October 7, 2025,

Comparing Business, Innovation, and Platform Ecosystems: A Systematic Review of the Literature - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed October 7, 2025,

Interfacing Intellectual property rights and Open innovation - WIPO, accessed October 7, 2025.

Patents and Open Innovation: Bad Fences Do Not Make Good Neighbors | Cairn.info, accessed October 7, 2025,

IP Strategy: How Patent Portfolios Can Secure Powerful Partnerships - Caldwell Law, accessed October 7, 2025,

Exploring the digital innovation ecosystem from the perspective of platform-based startups: a case study in the film industry - Emerald Insight, accessed October 7, 2025,

AI-driven Patent Portfolio Analysis - Effectual Services, accessed October 7, 2025,

The Future of Patent Portfolio Management: Trends and Innovations - PatentPC, accessed October 7, 2025,

AI-Driven Patent Portfolio Management: Maximizing ROI in Innovation - Patentskart, accessed October 7, 2025,

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Patent Lifecycle Management, accessed October 7, 2025.

Artificial Intelligence in Patent and Market Intelligence: A New Paradigm for Technology Scouting - arXiv, accessed October 7, 2025.

The Impact of AI on Patent Portfolio Management - Patent PC, accessed October 7, 2025,

Top 5 Mistakes by In-House Patent Counsel – And How to Avoid Them - KPPB LAW, accessed October 7, 2025,